COLLABORAZIONE E COMPRESENZA PROFESSORESSA ORIANA MAFFEO E PROFESSOR MARCO CASTELLI

CONSULTA LINK

http://wwrw.ushistory.org/betsy/index.html

A Biography of Betsy Ross

One year before William Penn founded Philadelphia in 1681, Betsy Ross’s great-grandfather, Andrew Griscom, a Quaker carpenter, had already emigrated from England to New Jersey.

Andrew was successful at his trade. He was also of firm Quaker belief, and he was inspired to move to Philadelphia to become an early participant in Penn’s “holy experiment.” He purchased 495 acres of land in the Spring Garden section north of the city of Philadelphia (the section would later be incorporated as part of the city), and received a plot of land within the city proper.

Griscom’s son and grandson both became respected carpenters as well. Both have their names inscribed on a wall at Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia, home of the oldest trade organization in the country.

Griscom’s grandson Samuel helped build the bell tower at the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall). He married Rebecca James who was a member of a prominent Quaker merchant family. It was not unusual for people in those days to have many children, so it is only somewhat surprising to learn that they had 17!

Elizabeth Griscom — also called Betsy, their eighth child and a fourth-generation American, was born on January 1, 1752.

Betsy went to a Friends (Quaker) public school. For eight hours a day she was taught reading, writing, and received instruction in a trade — probably sewing. After completing her schooling, Betsy’s father apprenticed her to a local upholsterer. Today we think of upholsterers primarily as sofa-makers and such, but in colonial times they performed all manner of sewing jobs, including flag-making. It was at her job that Betsy fell in love with another apprentice, John Ross, who was the son of an Episcopal assistant rector at Christ Church.

Quakers frowned on inter-denominational marriages. The penalty for such unions was severe — the guilty party being “read out” of the Quaker meeting house. Getting “read out” meant being cut off emotionally and economically from both family and meeting house. One’s entire history and community would be instantly dissolved. On a November night in 1773, 21-year-old Betsy eloped with John Ross. They ferried across the Delaware River to Hugg’s Tavern and were married in New Jersey. Her wedding caused an irrevocable split from her family. [It is an interesting parallel to note that on their wedding certificate is the name of New Jersey’s Governor, William Franklin, Benjamin Franklin’s son. Three years later William would have an irrevocable split with his father because he was a Loyalist against the cause of the Revolution.]

Less than two years after their nuptials, the couple started their own upholstery business. Their decision was a bold one as competition was tough and they could not count on Betsy’s Quaker circle for business. As she was “read out” of the Quaker community, on Sundays one could now find Betsy at Christ Church sitting in pew 12 with her husband. Some Sundays would find George Washington, America’s new commander in chief, sitting in an adjacent pew.

War Comes to Philadelphia

In January 1776, a disaffected British agitator living in Philadelphia for only a short while published a pamphlet that would have a profound impact on the Colonials. Tom Paine (“These are the times that try men’s souls”) wrote Common Sense which would swell rebellious hearts and sell 120,000 copies in three months; 500,000 copies before war’s end.

However, the city was fractured in its loyalties. Many still felt themselves citizens of Britain. Others were ardent revolutionaries heeding a call to arms.

Betsy and John Ross keenly felt the impact of the war. Fabrics needed for business were becoming hard to come by. Business was slow. John joined the Pennsylvania militia. While guarding an ammunition cache in mid-January 1776, John Ross was mortally wounded in an explosion. Though his young wife tried to nurse him back to health he died on the 21st and was buried in Christ Church cemetery.

In late May or early June of 1776, according to Betsy’s telling, she had that fateful meeting with the Committee of Three: George Washington, George Ross, and Robert Morris, which led to the sewing of the first flag. See more about this on the Betsy Ross and the American Flag page.

After becoming widowed, Betsy returned to the Quaker fold, in a way. Quakers are pacifists and forbidden from bearing arms. This led to a schism in their ranks. When Free, or Fighting Quakers — who supported the war effort — banded together, Betsy joined them. (The Free Quaker Meeting House, which still stands a few blocks from the Betsy Ross House, was built in 1783, after the war was over.)

Betsy would be married again in June 1777, this time to sea captain Joseph Ashburn in a ceremony performed at Old Swedes Church in Philadelphia.

During the winter of 1777, Betsy’s home was forcibly shared with British soldiers whose army occupied Philadelphia. Meanwhile the Continental Army was suffering that most historic winter at Valley Forge.

Betsy and Joseph had two daughters (Zillah, who died in her youth, and Elizabeth). On a trip to the West Indies to procure war supplies for the Revolutionary cause, Captain Ashburn was captured by the British and sent to Old Mill Prison in England where he died in March 1782, several months after the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia, the last major battle of the Revolutionary War.

After the War

Betsy learned of her husband’s death from her old friend, John Claypoole, another sailor imprisoned at the brutal Old Mill. In May of 1783, Betsy was married for the third time, the ceremony performed at Christ Church. Her new husband was none other than old friend John Claypoole. Betsy convinced her new husband to abandon the life of the sea and find landlubbing employment. Claypoole initially worked in her upholstery business and then at the U.S. Customs House in Philadelphia. The couple had five daughters (Clarissa Sidney, Susannah, Rachel, Jane, and Harriet, who died at nine months).

Betsy’s signature from the roster at the Free Quaker Meeting House, Philadelphia

After the birth of their second daughter, the family moved to bigger quarters on Second Street in what was then Philadelphia’s Mercantile District. Claypoole passed on in 1817 after years of ill health and Betsy never remarried. She continued working until 1827 bringing many of her immediate family into the business with her. After retiring, she went to live with her married daughter Susannah Satterthwaite in the then-remote suburb of Abington, PA, to the north of Philadelphia.

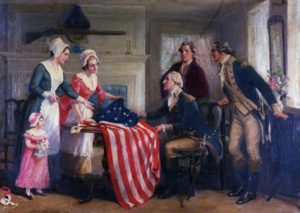

A vintage colour illustration of George Washington helping Betsy Ross to design the American flag as part of the Washington Birthday postcard series, printed circa 1900. (Photo by Popperfoto/Getty Images)

In 1834, there were only two Free Quakers still attending the Meeting House. It was agreed by Betsy and Samuel Wetherill’s son John Price Wetherill that the usefulness of their beloved Meeting House had come to an end. At that last meeting, Betsy watched as the door was locked, symbolizing the end of an era.

Betsy died on January 30, 1836, at the age of 84.

Betsy Ross Facts and Footnotes

- Betsy Ross was born January 1, 1752 and died at the age of 84 on January 30, 1836.

- Betsy had 7 children, 5 of whom lived to adulthood. She had no children with John Ross, however.

- At the age of 21, she eloped across the Delaware River to Gloucester, New Jersey, and was married at a tavern.

- She was the 8th of 17 children.

- She claimed to have done tailoring for George Washington.

- She has been buried in three different locations: Free Quaker burial ground at South 5th St. near Locust, Mt. Moriah Cemetery, and now on Arch Street in the courtyard adjacent to the Betsy Ross House.

- A major Philadelphia bridge is named in her honor.

Betsy Ross and the American Flag

Betsy would often tell her children, grandchildren, relatives, and friends of a fateful day, late in May of 1776, when three members of a secret committee from the Continental Congress came to call upon her. Those representatives, George Washington, Robert Morris, and George Ross, asked her to sew the first flag. George Washington was then the head of the Continental Army. Robert Morris, an owner of vast amounts of land, was perhaps the wealthiest citizen in the Colonies. Colonel George Ross was a respected Philadelphian and also the uncle of her late husband, John Ross.

Naturally, Betsy Ross already knew George Ross as she had married his nephew. Betsy was also acquainted with the great General Washington. Not only did they both worship at Christ Church in Philadelphia, but Betsy’s pew was next to George and Martha Washington’s pew. Her daughter recalled, “That she was previously well acquainted with Washington, and that he had often been in her house in friendly visits, as well as on business. That she had embroidered ruffles for his shirt bosoms and cuffs, and that it was partly owing to his friendship for her that she was chosen to make the flag.” (For full text, see Affidavits.)

In June 1776, brave Betsy was a widow struggling to run her own upholstery business. Upholsterers in colonial America not only worked on furniture but did all manner of sewing work, which for some included making flags. According to Betsy, General Washington showed her a rough design of the flag that included a six-pointed star. Betsy, a standout with the scissors, demonstrated how to cut a five-pointed star in a single snip. .

Until that time, colonies and militias used many different flags. Some are famous, such as the “Rattlesnake Flag” used by the Continental Navy, with its venomous challenge, “Don’t Tread on Me.”

Another naval flag had a green pine tree on a white background. The one shown here is the “Liberty Tree” flag.

Another naval flag had a green pine tree on a white background. The one shown here is the “Liberty Tree” flag.

Other flags were quite similar to Britain’s Union Jack or incorporated elements of it. A picture of the “Grand Union” flag is shown here.

Other flags were quite similar to Britain’s Union Jack or incorporated elements of it. A picture of the “Grand Union” flag is shown here.

This is not surprising. Many colonists considered themselves loyal subjects of Britain — many colonists came from Britain, and King George III ruled over the colonies.

On January 1, 1776, the Continental Army was reorganized in accordance with a Congressional resolution which placed American forces under George Washington’s control. On that New Year’s Day the Continental Army was laying siege to Boston which had been taken over by the British Army. Washington ordered the Grand Union flag hoisted above his base at Prospect Hill “in compliment of the United Colonies.”

In Boston, on that New Year’s Day, the Loyalists (supporters of Britain) had been circulating a recent King George speech, offering the Continental forces favorable terms if they laid down their arms. These Loyalists were convinced that the King’s speech had impressed the Continentals into surrendering — as a sign of the Continentals’ “surrender,” the Loyalists mistook the flying of the Grand Union flag over Prospect Hill as a show of respect to King George. In fact, however, the Continentals knew nothing of the speech until later. Washington wrote in a letter dated January 4, “By this time, I presume, they begin to think it strange we have not made a formal surrender of our lines.”

Obviously a new flag was needed.

According to Betsy Ross’s dates and sequence of events, in May the Congressional Committee called upon her at her shop. She finished the flag either in late May or early June 1776. In July, the Declaration of Independence was read aloud for the first time at Independence Hall. Amid celebration, bells throughout the city tolled, heralding the birth of a new nation.

Much suffering and loss of life would result, however, before the United States would completely sever ties with Britain. Betsy Ross herself lost two husbands to the Revolutionary War. During the conflict the British appropriated her house to lodge soldiers. Through it all she managed to run her own upholstery business (which she continued operating for several decades after the war) and after the soldiers left, she wove cloth pouches which were used to hold gunpowder for the Continentals. (See The Story of Betsy Ross’s Life for more information.)

On June 14, 1777, the Continental Congress, seeking to promote national pride and unity, adopted the national flag. “Resolved: that the flag of the United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.”

Flag Picture Gallery

American ships in New England waters flew a “Liberty Tree” flag in 1775. It shows a green pine tree on a white background, with the words, “An Appeal to Heaven.”

American ships in New England waters flew a “Liberty Tree” flag in 1775. It shows a green pine tree on a white background, with the words, “An Appeal to Heaven.”

The Continental Navy used this flag, with the warning, “Don’t Tread on Me,” upon its inception.

The Continental Navy used this flag, with the warning, “Don’t Tread on Me,” upon its inception.

The “Grand Union” shown here is also called The “Cambridge Flag.” It was flown over Prospect Hill, overlooking Boston, January 1, 1776. In the canton (the square in the corner) are the crosses of Saint Andrew and Saint George, borrowed from the British flag.

The “Grand Union” shown here is also called The “Cambridge Flag.” It was flown over Prospect Hill, overlooking Boston, January 1, 1776. In the canton (the square in the corner) are the crosses of Saint Andrew and Saint George, borrowed from the British flag.

The “Betsy Ross” flag. The Flag Resolution did not specify the arrangement of the stars nor the specific proportions of the flag. So many 13-star flags were used, as seen from the next several pictures.

The “Betsy Ross” flag. The Flag Resolution did not specify the arrangement of the stars nor the specific proportions of the flag. So many 13-star flags were used, as seen from the next several pictures.

Another 13-star flag, in the 3-2-3-2-3 pattern.

Another 13-star flag, in the 3-2-3-2-3 pattern.

The Guilford Flag.

The Guilford Flag.

The Serapis Flag.

The Serapis Flag. According to some accounts, two famous flags were flown at the Battle of Bennington. One, shown here, is called the Bennington Flag or the Fillmore Flag. The story goes that Nathaniel Fillmore took this flag home from the battlefield, and the flag was passed down through generations of Fillmores, including Millard, and today it can be seen at Vermont’s Bennington Museum. Most experts doubt this story and date the flag to about 1820. The other (not pictured) has a green field and a blue canton with 13 gold-painted stars arranged in rows. General John Stark gave his New Hampshire troops a rallying speech that would be the envy of any football coach today. He said, “My men, yonder are the Hessians. They were brought for seven pounds and ten pence a man. Are you worth more? Prove it. Tonight, the American flag floats from yonder hill or Molly Stark sleeps a widow!”

According to some accounts, two famous flags were flown at the Battle of Bennington. One, shown here, is called the Bennington Flag or the Fillmore Flag. The story goes that Nathaniel Fillmore took this flag home from the battlefield, and the flag was passed down through generations of Fillmores, including Millard, and today it can be seen at Vermont’s Bennington Museum. Most experts doubt this story and date the flag to about 1820. The other (not pictured) has a green field and a blue canton with 13 gold-painted stars arranged in rows. General John Stark gave his New Hampshire troops a rallying speech that would be the envy of any football coach today. He said, “My men, yonder are the Hessians. They were brought for seven pounds and ten pence a man. Are you worth more? Prove it. Tonight, the American flag floats from yonder hill or Molly Stark sleeps a widow!”

Cowpens Flag. According to some sources, this flag was first used in 1777. It was used by the Third Maryland Regiment. There was no official pattern for how the stars were to be arranged. The flag was carried at the Battle of Cowpens, which took place on January 17, 1781, in South Carolina. The actual flag from that battle hangs in the Maryland State House.

Cowpens Flag. According to some sources, this flag was first used in 1777. It was used by the Third Maryland Regiment. There was no official pattern for how the stars were to be arranged. The flag was carried at the Battle of Cowpens, which took place on January 17, 1781, in South Carolina. The actual flag from that battle hangs in the Maryland State House.

Vermont and Kentucky joined the union in 1791 and 1792. This flag with 15 stars and 15 stripes, was adopted by a Congressional act of 1794. The flag became effective May 1, 1795.

Vermont and Kentucky joined the union in 1791 and 1792. This flag with 15 stars and 15 stripes, was adopted by a Congressional act of 1794. The flag became effective May 1, 1795.

By 1818, the union consisted of 20 states. A Congressional act mandated that the number of stripes be fixed at 13 and that one new star was to be added for each new state, the July 4 following its admission. However, nothing was written about what arrangement the stars should be in. This and the following two flags were all used simultaneously.

By 1818, the union consisted of 20 states. A Congressional act mandated that the number of stripes be fixed at 13 and that one new star was to be added for each new state, the July 4 following its admission. However, nothing was written about what arrangement the stars should be in. This and the following two flags were all used simultaneously.

1818 flag (see above).

1818 flag (see above).

And another 1818 flag (see above). This was called the “Grand Star” flag.

And another 1818 flag (see above). This was called the “Grand Star” flag.

Commenti recenti