Le origini

La storia di Venezia parte dall’esigenza dei Veneti di trovare un luogo che potesse garantire protezione in caso di eventuali invasioni nemiche, specialmente da parte degli Ostrogoti e dei Longobardi, e la laguna dove ora sorge Venezia soddisfava i requisiti per via del suolo paludoso e delle acque stagnanti. Prima di diventare una vera e propria Repubblica, Venezia fu governata dall’Esarca di Ravenna con la protezione dell’Impero Bizantino. La Repubblica di Venezia fu fondata nel 697 da Paoluccio Anafesto, primo doge della storia, che era stato eletto dalle famiglie più ricche. Aveva sede sull’isola di Rialto, il più antico nucleo della città, famoso per il mercato e per il celebre ponte.

Ma come mai la potenza della Repubblica di Venezia riuscì a durare ben 1100 anni? Quali erano i punti di forza che le permisero di espandersi in gran parte dell’Italia nord-orientale, Istria, Dalmazia, Peloponneso, Creta e Cipro, nonché in diverse città e porti del Mediterraneo Orientale?

Gli scambi commerciali: nasce l’emporio

Poiché le isole erano troppo piccole per poter fornire una produzione agricola sufficiente, la popolazione dovette adattarsi e trovare altre risorse utili per lo scambio commerciale. Qui entrò in gioco il sale, abbondante in tutto il territorio per la presenza del mare, che cominciò a essere scambiato con il grano. Questo scambio determinò l’inizio dell’economia lagunare e l’origine della navigazione fluviale, in Laguna, nel Po e nelle zone costiere che si affacciavano sul mare Adriatico. Tuttavia il sale non tardò a rivelarsi insufficiente, crebbero le esigenze e si diffuse la richiesta di olio, vino, carne e spezie. L’esportazione e l’importazione di questi prodotti necessitavano però di una struttura più ampia e complessa di un semplice porto. Così i Veneziani pensarono bene di costruire un vero e proprio emporio degno di questo nome: la strategia commerciale che permise loro di prosperare e sopraffare le altre potenze marittime, consisteva nel vietare il transito nel porto. Grazie a questo ingegno, tutte le merci provenienti da Ovest che volevano passare per Venezia, avrebbero dovuto essere vendute ai commercianti veneziani pagando i diritti d’ingresso; allo stesso modo chi voleva acquistare prodotti orientali e occidentali, si recava a Venezia per comprare direttamente dai Veneziani. Per rendere l’emporio il più efficiente possibile, era necessario un continuo monitoraggio della domanda e dell’offerta, che non era affatto facile.

“[…] Le merci scorrono per quella nobile città come l’acqua dalle sorgenti […] da ogni luogo giungono merci e mercanti, che comperano le merci che preferiscono e le fanno portare al loro paese” Cit. Martin da Canal, cronista veneziano

Come ci fa notare Martin da Canal, l’emporio realtino era un vero e proprio crogiolo di gruppi familiari, che attraeva svariate e numerose casate provenienti dai centri minori del Dogado, una delle tre grandi aree amministrative in cui si divideva la Repubblica di Venezia, che comprendeva l’antico Ducato di Venezia e le lagune situate tra le foci del Po e dell’Isonzo. L’emporio aveva generato una fama tanto vasta da conquistare anche l’interesse di rinomati mercanti con sede nelle Marche, in Romagna e in Istria. Questo ci permette di capire quanto l’espansione del traffico veneziano divenne importante per la prosperità della Repubblica.

Le mude veneziane

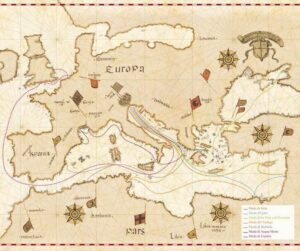

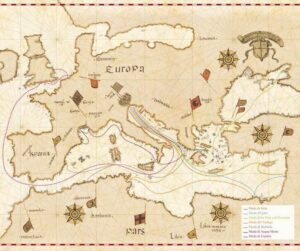

Se si vuole parlare di una potenza marittima come quella in questione, non si possono non citare le cosiddette “mude”, convogli di battelli che navigano in gruppo o, usando il termine mercantile, di conserva, che battono la stessa rotta più e più volte all’anno. Sicuramente le mude veneziane preferivano le destinazioni bizantine, ma poiché nel 1171 queste divennero inaccessibili, si dovette guardare verso nuove rotte. Quella che segue è una mappa che illustra le rotte commerciali delle mude.

- Nella seconda metà del secolo XII tra le rotte più diffuse era presente quella con destinazione finale la Terra Santa. Data la cospicua richiesta di esportazione del grano per quanto riguarda gli alimenti, inizialmente furono le Puglie a occupare il posto preminente in questa corrente di traffici. Successivamente, attorno al 1170, si affiancarono anche la Calabria, Palermo e soprattutto Messina. Questo era l’ultimo scalo in Italia prima di proseguire il percorso verso Israele, Palestina ed Egitto. Nel tragitto le navi imbarcavano anche cotone perché era destinato all’industria tessile lombarda.

- Nell’Adriatico i tragitti potevano essere due: uno era lungo la costa orientale e la Dalmazia, ma aveva ostacoli per la navigazione non da poco, quali i litorali piatti e sabbiosi ma soprattutto l’assenza di ripari; l’altro percorso, decisamente più gradito ai marinai per via delle acque profonde e dei porti naturali, era quello che costeggiava la sponda italiana. Questa tratta permettava inoltre di passare per la Sicilia, nel Mediterraneo e mettere la prua alla volta dell’Egitto

- Per raggiungere la Terra Santa si poteva anche optare per la rotta dalmata che permetteva di toccare le terre di Rodi, le isole e la costa dell’Asia Minore.

- La rotta per Costantinopoli aveva anch’essa due varianti, una passante per Rodi e Asia Minore, e un altra che prevedeva la circumnavigazione della Grecia. Apparentemente questa sembrerebbe più svantaggiosa, ma a seguito dell’assunzione di potere da parte di Venezia di Creta e di Negroponte, questi scali offrivano una protezione migliore

Le mude potevano assumere nomi diversi anche in base al periodo di partenza delle navi. Troviamo ad esempio la “mudua pascae Resurrectionis Domini” (Pasqua – primavera), la “mudua aestatis” (estate), la “mudua mensis augusti” (agosto) e infine la “mudua hiberni” (inverno).

L’arsenale

Siamo ora arrivati all’altro aspetto che assicurò la prosperità alla città con patrono San Marco: l’arsenale. Le motivazioni che spinsero i Veneziani a costruire questo pezzo di storia furono dettate dalla maggiore esigenza di sviluppo della cantieristica, un’attività strategica che permise loro di imporre il controllo su gran parte del Mediterraneo. Come ogni potenza marittima, la Serenissima aveva una grande richiesta di navi, che necessitavano di un luogo per la costruzione. Quello che andiamo ad esaminare è il più antico arsenale della storia, che col tempo si è evoluto, si è espanso, e ha dato vita a navi famose in tutto il Mediterraneo. Si stima che questo cantiere navale nei periodi di piena attività produttiva desse lavoro ogni giorno a 1500-2000 arsenalotti – così erano chiamati gli artigiani e i lavoratori dell’arsenale – con picchi di 4500-5000 lavoratori. Tuttavia nel suo periodo di massimo sviluppo è probabile che gli addetti superassero quota 16000.

Come l’emporio, parimenti l’arsenale acquisì fama nel corso degli anni. Dopo avere avuto la possibilità di visitarlo, Dante stesso decise di riservargli uno frammento nella Divina Commedia, nel canto XXI dell’Inferno:

Quale ne l’arzanà de’ Viniziani

bolle l’inverno la tenace pece

a rimpalmare i legni lor non sani

ché navicar non ponno – in quella vece

chi fa suo legno novo e chi ristoppa

le coste a quel che più vïaggi fece

chi ribatte da proda e chi da poppa

altri fa remi e altri volge sarte

chi terzeruolo e artimon rintoppa

Il termine “arsenale” deriva dall’arabo darassina’ah, che a seguito di mutamenti fonetici è diventato arsenà tra i Veneziani. Al termine arabo possiamo ricollegare un’altra parola, “darsena”, che indicava i canali all’interno dell’arsenale.

Sebbene alcuni studiosi riconducano la data di fondazione al 1104, è più accreditato far riferimento all’arco temporale che copre indicativamente i primi anni del secolo XII. L’arsenale cronologicamente definito “vecchio” giace a ridosso del Bacino di San Marco, tra la sede vescovile del castello di Olivolo e la sede Ducale e politica di San Marco. Il vantaggio di aver scelto questa zona fu determinato dai territori circostanti, i quali essendo liberi avrebbero potuto essere usati, come avverrà, per l’estensione del cantiere. Il primo ampliamento diede spazio alla costruzione di nuovi “tezoni” o “tese” (immagine sopra), capannoni in muratura portante con coperture in legno e adibiti alla costruzione di navi da guerra, oltre a officine di remi, corderie e depositi di pece; inoltre permise di aprire il canale delle Stoppare verso il lago San Daniele.

Tra i vari ampliamenti che si susseguono nel corso degli anni, uno spicca all’occhio per le sue innovazioni: ci troviamo nel 1460. Lungo lo “Stradal de Campagna” si edificarono il nucleo d’origine della Sala d’Armi, la Sala d’Artiglieria, il deposito delle palle di cannone, l’officina delle armi e due tezoni acquatici. Non dimentichiamo la celebre costruzione della Porta da Terra, con le due ben note figure di leoni, e l’ingresso monumentale.

Dal 1500 proseguirono gli scavi delle darsene, l’innalzo della polveriera, fino ad arrivare al 1544, anno in cui si completano 16 tezoni sul lato Nord. Il 1569 ha particolare importanza perché terminarono sia la costruzione delle mura perimetrali, sia lo scavo della Darsena delle Galeazze e i tenzoni coperti per la costruzione di questa nuova e assai potente tipologia di nave da guerra. I risultati non tardarono a venire, e nel 1571 i Veneziani riportarono una vittoria schiacciante sulla flotta ottomana nella battaglia di Lepanto, dimostrando l’evidente supremazia dell’arsenale veneziano.

Le navi

L’imbarcazione più famosa è certamente la galea (dal greco galeos=squalo), anche chiamata galera, che poteva avere dagli uno ai tre alberi con rispettivi apparati velici. Esistevano anche delle sottocategorie di galee, come ad esempio la galea sottile, la galea grossa da merchado e la galea bastarda, che in quanto a dimensioni era a metà tra le due elencate precedentemente, ma che poteva ospitare il “Capitano Generale da mar”, rendendola così una nave bandiera. L’equipaggio di queste navi poteva variare: generalmente era formato da rematori e schiavi che erano incatenati al banco di voga (in caso di arrembaggio non si sarebbero potuti salvare), oppure, come nelle galee dei “buonavoglia”, i volontari assoldati a stipendio potevano essere liberati. A bordo delle navi potevamo trovare anche altre figure quali barbieri, sacerdoti, musicisti, soldati, cannonieri ecc.

Dalla seconda metà del XVI secolo inizia la produzione di una nuova tipologia di nave, la galeazza, un naviglio più grande dotato di cannoni. Qui entrano in gioco gli artiglieri tedeschi, che da un po’ di tempo erano al servizio della Repubblica, e che grazie alle loro tecniche avevano reso ottimale l’artiglieria a bordo. Un altro pregio di questa imbarcazione era la sua stazza, altezza e forma tondeggiante, che permetteva di supportare agevolmente il rinculo dovuto ai cannoni, ma che portava tuttavia anche dei contro, ossia l’assai difficoltosa manovrabilità.

Dalla seconda metà del XVI secolo inizia la produzione di una nuova tipologia di nave, la galeazza, un naviglio più grande dotato di cannoni. Qui entrano in gioco gli artiglieri tedeschi, che da un po’ di tempo erano al servizio della Repubblica, e che grazie alle loro tecniche avevano reso ottimale l’artiglieria a bordo. Un altro pregio di questa imbarcazione era la sua stazza, altezza e forma tondeggiante, che permetteva di supportare agevolmente il rinculo dovuto ai cannoni, ma che portava tuttavia anche dei contro, ossia l’assai difficoltosa manovrabilità.

La nave simbolo dei Veneziani era il Bucintoro, un naviglio da parata ornato con lussosi intagli e sculture dorate, destinato a pubbliche solenni cerimonie o a navigazione di diporto. Una tradizione prevedeva il lancio di un anello dal ponte superiore del Bucintoro da parte del Doge nelle acque antistanti San Marco, a simboleggiare l’unione della Serenissima con il Mare e il dominio sull’Adriatico, invocando allo stesso tempo la sua protezione. Questa nave fu distrutta da Napoleone, di sua spontanea iniziativa, per simboleggiare l’odio verso la Repubblica. Inizialmente la sua idea era quella di trasportarla in Francia, come del resto tutti gli altri beni all’interno dell’arsenale, ma poiché necessitava di 150 vogatori e 50 marinai, evidentemente non disponibili, decise di cambiare piano. Prima la fece trainare dietro a S. Giorgio per fondere le statue auree, in seguito fece trasformare lo scafo in una prigione per i restanti sostenitori di San Marco. Successivamente, dopo un primo tentativo fallito, fece bruciare completamente il Bucintoro, un esempio di successo veneziano ormai perduto. Alcuni sostenevano che la nave fosse stata distrutta dalla municipalità giacobina veneziana, ma sebbene questa fosse in grado di compiere un gesto di tale portata (basti vedere Ugo Foscolo che voleva bruciare l’intera Venezia pur di non darla in mano agli Austriaci), si ritenne non essere la colpevole della distruzione di questo bene.

The origins

The history of Venice starts from the need of the Venetians to find a place that could guarantee protection in the event of an enemy invasion, especially by the Ostrogoths and the Lombards, and the lagoon where Venice now stands met the requirements due to the marshy soil and the stagnant water . Before becoming a real Republic, Venice was ruled by the Exarch of Ravenna with the protection of the Byzantine Empire. The Republic of Venice was founded in 697 by Paoluccio Anafesto, the first doge in history, who had been elected by the richest families. It was based on Rialto island, the oldest part of the city, famous for the market and the renowned bridge.

But why did the power of the Republic of Venice last 1100 years? What were the strengths that allowed it to expand in most of north-eastern Italy, Istria, Dalmatia, Peloponnese, Crete and Cyprus, as well as in many cities and harbours of the Eastern Mediterranean?

The trades: the emporium is born

As the islands were too small to provide sufficient agricultural production, the population had to adapt and find other resources useful for trading. Here salt came into play, abundant throughout the territory due to the presence of the sea, began to be exchanged for wheat. This exchange determined the beginning of the lagoon economy and the origin of river navigation, in the lagoon, in the Po and in the coastal areas that overlooked the Adriatic Sea. However, salt didn’t take long to prove insufficient, the needs increased and the demand for oil, wine, meat and spices spread. The export and import of these products required a larger and more complex structure than a simple harbor. So the Venetians thought it best to build a veritable emporium worthy of the name: the business strategy that enabled them to thrive and overwhelm the other maritime powers, was to prohibit the transit in the harbor. Thanks to this smart idea, all the goods coming from the West that wanted to pass through Venice, would have to be sold to Venetian traders paying the entrance fees; in the same way, those who wanted to buy oriental and western products would go to Venice to buy directly from the Venetians. To make the emporium as efficient as possible, it needed a continuous monitoring of the application and offer , which wasn’t easy at all.

“[…] Goods flow through that noble city like water from springs […] goods and merchants arrive from everywhere, these buy the goods they prefer and have them brought to their country” Cit. Martin da Canal, Venetian chronicler

As Martin da Canal points out, the emporium of Rialto was a real melting pot of family groups, which attracted various and numerous families from the smaller centers of the Dogado, one of the three large administrative areas into which the Republic of Venice was divided, which included the ancient Duchy of Venice and the lagoons located between the mouths of the Po and the Isonzo. The emporium had generated such a vast fame that it also won the interest of renowned merchants based in the Marche, Romagna and Istria. This allows us to understand how important the expansion of Venetian traffic became for the prosperity of the Republic.

The Venetian Mude

If we want to talk about a maritime power like the one in question, we cannot fail to mention the so-called “mude”, convoys of boats that sail in groups or, using the merchant term, of conserve, which sail the same route over and over again during the year. Certainly the Venetian Mude preferred Byzantine destinations, but since in 1171 these became inaccessible, it was necessary to look towards new routes. The following map illustrates the trade routes of the mude.

- In the second half of the 12th century, one of the most common routes was the one with the Holy Land as final destination. Given the conspicuous demand for the export of grain as regards food, initially it was Puglia that occupied the pre-eminent place in this current of trade. Subsequently, around 1170, Puglia was joined by Calabria, Palermo and especially Messina. This was the last stop in Italy before continuing the route to Israel, Palestine and Egypt. On the way the ships also used to load cotton because it was destined for the Lombard textile industry.

- In the Adriatic there could be two routes: one was along the eastern coast and Dalmatia, but it had significant obstacles for navigation, such as flat and sandy coasts, but above all the absence of shelters; the other route, much more pleasing to sailors because of the deep waters and natural ports, was the one that ran along the Italian shore. This route also allowed to pass through Sicily, in the Mediterranean and put the bow towards Egypt

- To reach the Holy Land it was also possible to opt for the Dalmatian route, which allowed to touch the lands of Rhodes, the islands and the coast of Asia Minor.

- The route to Constantinople also had two variants, one passing through Rhodes and Asia Minor, and another involving the circumnavigation of Greece. Apparently this would seem more disadvantageous, but following the takeover of power by Venice of Crete and Negroponte, these ports of call offered better protection.

The mude could also take different names based on the period of departure of the ships. For example, we find the “mudua pascae Resurrectionis Domini” (Easter – spring), the “mudua aestatis” (summer), the “mudua mensis augusti” (August) and finally the “mudua hiberni” (winter).

The arsenal

We have now arrived to the other aspect that ensured the prosperity of the city with San Marco as patron: the arsenal. The reasons that pushed the Venetians to build this piece of history were dictated by the greater need for the development of shipbuilding, a strategic activity that allowed them to impose control over much of the Mediterranean. Like any maritime power, the Serenissima had a great demand for ships, which needed a place for construction. What we are going to examine is the oldest arsenal in history, which has evolved over time, expanded, and gave birth to ships famous throughout the Mediterranean. It is estimated that this shipyard in the periods of full production activity employed 1500-2000 “arsenalotti” – name for the craftsmen and workers of the arsenal – every day, with peaks of 4500-5000 workers. However in its period of maximum development it is probable that the employees exceeded 16,000.

Like the emporium, the arsenal also gained fame over the years. After having had the opportunity to visit it, Dante himself decided to reserve a fragment for it in the Divine Comedy, in canto XXI of Hell:

As in the Arsenal of the Venetians

Boils in the winter the tenacious pitch

To smear their unsound vessels o’er again,For sail they cannot; and instead thereof

One makes his vessel new, and one recaulks

The ribs of that which many a voyage has made;One hammers at the prow, one at the stern,

This one makes oars, and that one cordage twists,

Another mends the mainsail and the mizzen;

The term “arsenal” comes from the Arabic darassina’ah, which as a result of phonetic changes has become arsenà among the Venetians. We can connect another word to the Arabic term, “darsena” (italian for dock), which indicated the canals within the arsenal.

The term “arsenal” comes from the Arabic darassina’ah, which as a result of phonetic changes has become arsenà among the Venetians. We can connect another word to the Arabic term, “darsena” (italian for dock), which indicated the canals within the arsenal.

Although some scholars trace the foundation date back to 1104, it’s more accredited to refer to the time span that roughly covers the first years of the 12th century. The arsenal chronologically defined as “old” lies close to the San Marco Basin, between the bishopric of the castle of Olivolo and the Ducal and political seat of San Marco. The advantage of having chosen this area was determined by the surrounding territories, which could have been used because they were free, as will happen, for the extension of the construction site. The first extension gave space to the construction of new “tezoni” or “tese” (image above), load-bearing masonry sheds with wooden roofs and used for the construction of warships, as well as oar workshops, ropes and pitch deposits; it also allowed the Stoppare canal to be opened towards Lake San Daniele.

Among the various extensions that have followed one another over the years, one stands out for its innovations: we are in 1460. Along the “Stradal de Campagna” the original nucleus of the Arms Room was built, the Artillery Room, the cannonball depot, the weapons workshop and two aquatic tezoni. Let’s not forget the famous construction of the “Porta da Terra”, with the two well-known figures of lions, and the monumental entrance.

From 1500 had continued the excavations of the docks, the raising of the powder magazine, up to 1544, the year in which 16 tezoni were completed on the north side. 1569 has particular importance because the construction of the perimeter walls, the excavation of the Darsena delle Galeazze and the covered tezoni for the construction of this new and very powerful type of warship were completed. The results were not long in coming, and in 1571 the Venetians delivered a landslide victory over the Ottoman fleet in the battle of Lepanto, demonstrating the evident supremacy of the Venetian arsenal.

The ships

The most famous boat is certainly the galley (from the Greek galeos = shark), also called galera, which could have from one to three masts with respective sail systems. There were also sub-categories of galleys, such as the thin galley, the large merchado galley and the bastard galley, which in terms of size was halfway between the two listed above, but which could accommodate the “Captain General from the sea”, thus making it a flag ship. The crew of these ships could vary: generally it consisted of oarsmen and slaves who were chained to the rowing bench (in case of enemy boarding they couldn’t be saved), or, as in the galleys of the “buonavoglia”, the volunteers hired with a salary could be released. Aboard the ships we could also find other figures such as barbers, priests, musicians, soldiers, gunners, etc.

From the second half of the sixteenth century begins the production of a new type of ship, the “galeazza”, a larger ship equipped with cannons. Here the German artillerymen come into play, who for some time had been in the service of the Republic, and who thanks to their techniques had made the artillery on board optimal. Another advantage of this boat was its size, height and rounded shape, which made it possible to easily support the recoil due to the guns, but which however also brought cons, such as the very difficult maneuverability.

From the second half of the sixteenth century begins the production of a new type of ship, the “galeazza”, a larger ship equipped with cannons. Here the German artillerymen come into play, who for some time had been in the service of the Republic, and who thanks to their techniques had made the artillery on board optimal. Another advantage of this boat was its size, height and rounded shape, which made it possible to easily support the recoil due to the guns, but which however also brought cons, such as the very difficult maneuverability.

The symbolic ship of the Venetians was the Bucintoro, a parade ship adorned with luxury carvings and gilded sculptures, intended for public solemn ceremonies or for pleasure sailing. One tradition involved the launch of a ring from the upper deck of the Bucintoro by the Doge in the waters in front of San Marco, to symbolize the union of the Serenissima with the sea and dominion over the Adriatic, at the same time invoking its protection. This ship was destroyed by Napoleon, on his own initiative, to symbolize hatred of the Republic. Initially his idea was to transport it to France, like all the other goods in the arsenal, but since he needed 150 rowers and 50 sailors, clearly not available, he decided to change plans. First he had it towed behind S. Giorgio to melt the golden statues, later, he had the hull transformed into a prison for the remaining supporters of San Marco. Subsequently, after a first failed attempt, he completely burned the Bucintoro, an example of Venetian success now lost. Some claimed that the ship had been destroyed by the Venetian Jacobin municipality, but although it would have been able to make a gesture of such magnitude (just see Ugo Foscolo who wanted to burn the whole Venice in order not to give it to the Austrians), it was believed to not be guilty of the destruction of this good.

ARTICOLO DI SATTA ALESSANDRO DELLA CLASSE III A DEL LICEO CLASSICO

SITOGRAFIA:

https://www.scoprivenezia.com/storia

https://www.settemuse.it/viaggi_italia_veneto/venezia_guida_storia.htm

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Repubblica_di_Venezia

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rialto_(Venezia)

https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/i-meccanismi-dei-traffici_%28Storia-di-Venezia%29/

https://www.studenti.it/repubblica-venezia-storia-cronologia-caratteristiche-della-serenissima.html

http://www.viagginellastoria.it/archeoletture/luoghi/1940venezia.htm

https://www.metropolitano.it/arsenale-di-venezia-storia/

https://www.comune.venezia.it/it/arsenaledivenezia

https://www.comune.venezia.it/it/content/storia-dellarsenale-venezia

https://www.informagiovani-italia.com/arsenale_venezia.htm

https://www.smingegneria.it/arsenale-ve/

http://www.veneziamuseo.it/ARSENAL/schede_arsenal/stradal_campagna.htm

https://www.venetostoria.com/?p=6559

https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/bucintoro_%28Enciclopedia-Italiana%29/

http://www.everypoet.com/archive/poetry/dante/dante_i_21.htm

Commenti recenti