LINK CONSIGLIATI:

https://www.focus.it/scienza/scienze/il-giardino-piu-velenoso-del-mondo

https://biografieonline.it/morti.htm?causa=avvelenamento

http://www.enciclopediadelledonne.it/biografie/lucrezia-borgia/

Il breve passo da assassini a vittime

Presenti nei banchetti greci e romani, furono perfezionati nell’uso dalla cultura islamica e nel Medioevo risultarono grandi protagonisti anche tra i troni papali. Incidenti e assassinii iniziarono ad essere scambiati per indigestioni o malattie di dubbia provenienza.

Fin dall’antichità, quindi, le stesse specifiche piante impiegate per la produzione di principi con azione farmacologica, sono utilizzate anche per la realizzazione di veleni terribili; infatti, come sosteneva Paracelso, “è la dose a fare il veleno”. Alcune piante sono specie esotiche, ma per la maggior parte si tratta di esemplari insospettabili che crescono tranquillamente nel prato di casa. Un esempio è l’oleandro (Nerium oleander), simbolo di morte in molte culture: ogni sua parte può provocare nausea, vomito e alterazioni del ritmo cardiaco; cinque foglie, ingerite, bastano per uccidere. Piante tossiche in cui è facile imbattersi sono anche la peonia, utilizzata nell’antichità per provocare l’aborto, il mughetto, l’ortensia e il narciso.

Alcuni esemplari risultano essere più affidabili e letali di altri.

- Aconito (Aconitum napellus)

L’aconitina, suo principio attivo, è uno dei veleni più potenti che si conoscano: si può ridurre facilmente in una polvere color bianco-giallo, dal sapore pungente, più facile da sciogliere nell’alcol che nell’acqua. La dose letale per un uomo è di 5 mg per Kg di massa corporea. La morte avviene in poche ore, a seguito di crampi violenti e perdita completa della coscienza. Non si conoscono antidoti.

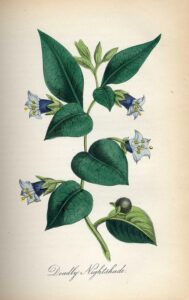

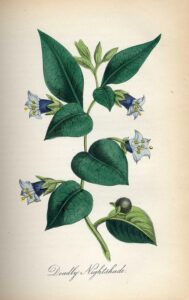

- Belladonna (Atropa belladonna)

Pianta che cresce sui muri e fiorisce nei mesi estivi. Tutte le sue parti sono velenose, ma in particolare le bacche dal gusto dolciastro. Agisce specialmente sul cervello e i sintomi dell’avvelenamento insorgono in tempi molto rapidi. La morte avviene per paralisi, generalmente dopo 24-36 ore dell’ingestione.

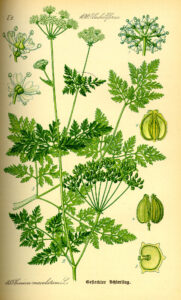

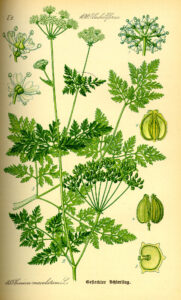

- Cicuta (Conium maculatum)

Pianta perenne dalle foglie molto grandi e dai piccoli fiori bianchi. Il principio tossico è la cicutina, un liquido oleoso, giallastro, di odore acuto e sgradevole, poco solubile nell’acqua, molto nell’alcol. Il veleno è paralizzante e la morte avviene per asfissia a circa 3-6 ore dall’assunzione.

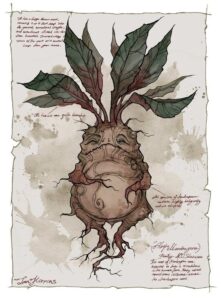

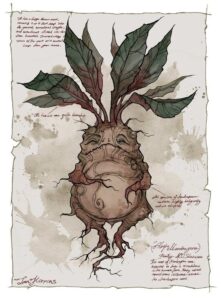

- Mandragora (Mandragora officinarum)

Considerata tradizionalmente una creatura a metà tra il regno vegetale e quello animale, si credeva nascesse dallo sperma degli impiccati e che il suo “pianto” potesse uccidere un uomo. In realtà, le sue radici contengono alcaloidi tossici che, assunti in dosi massicce, provocano tachicardia, allucinazioni, convulsioni e morte.

In Europa, nel Medioevo e sino alla metà del secolo XIX, le sostanze tossiche più usate furono specialmente di origine vegetale, ma la conoscenza si estese ben presto anche a veleni di origine minerale, nel momento in cui divennero facilmente disponibili i sali di rame e di piombo e gli acidi forti. Fattori industriali vari fecero poi predominare ora l’uno ora l’altro veleno.

- Arsenico

La sostanza generalmente usata come veleno, comunemente in forma minerale, è l’arsenico bianco (triossido arsenioso), chiamato anche “polvere degli eredi”. Ben solubile in acqua e privo di odore e sapore, “brucia” letteralmente l’intestino, provocando la morte dopo una lunga sofferenza.

- Cianuro

Sale derivato dall’acido cianidrico. Blocca il trasporto di ossigeno alle cellule, provocando la morte per soffocamento o una perdita di coscienza istantanea, con conseguente arresto cardiaco. Nella maggior parte dei casi, la vittima di un avvelenamento da cianuro emana un odore caratteristico di mandorle amare.

Ciò che rende così celebri questi e altri veleni sono sicuramente le occasioni in cui furono utilizzati: più nota è la vittima di un veleno, più aumenta la sua fama. E’ pertanto opportuno trattare anche delle principali morti di cui questi sarebbero responsabili, almeno molto probabilmente. Secondo le fonti di cui disponiamo, infatti, ci è soltanto concesso fare supposizioni, ogni decesso per avvelenamento non viene mai dato per certo.

Nel caso della cicuta, quando sentiamo nominare questo veleno pensiamo immediatamente al grande filosofo Socrate, che la usò per togliersi la vita, obbligato dal governo della sua stessa città, Atene. Platone, nel sessantaseiesimo capitolo del Fedone, racconta così gli ultimi istanti del maestro, dopo che ebbe bevuto il veleno, e la sua morte:

Egli, allora, andò un po’ su e giù per la stanza, poi disse che si sentiva le gambe farsi pesanti e cosi si stese supino come gli aveva detto l’uomo del veleno il quale, intanto, toccandolo dì quando in quando, gli esaminava le gambe e i piedi’e a un tratto, premette forte un piede chiedendogli se gli facesse male. Rispose di no. Dopo un po’ gli toccò le gambe, giù in basso e poi, risalendo man mano, sempre più in su, facendoci vedere come si raffreddasse e si andasse irrigidendo. Poi, continuando a toccarlo: «Quando gli giungerà al cuore,» disse, «allora, sarà finita.» Egli era già freddo, fino all’addome, quando si scoprì (s’era, infatti, coperto) e queste furono le sue ultime parole: «Critone, dobbiamo un gallo ad Asclepio, dateglielo, non ve ne dimenticate.» […] Dopo un po’ ebbe un sussulto. L’uomo lo scoprì: aveva gli occhi fissi.

L’offerta di un gallo era il ringraziamento tradizionale di chi guariva da una malattia al dio della medicina, Asclepio. Il dono del gallo fa riferimento a un contesto religioso: la parte migliore di Socrate non è morta, ma ha resistito alla sfida dell’esistenza storica individuale e continua a vivere; per aver assistito Socrate e i suoi amici nella prova il dio della medicina merita un ringraziamento.

Tommaso d’Aquino

All’età di 18 anni, contro la volontà del padre e dei fratelli, entrò nell’ordine dei Predicatori di San Domenico. Fu teologo, intellettuale, docente di filosofia a Parigi e scrittore. La sua opera più celebre è la Summa Theologiae, scritto che, come tutti gli altri realizzati da Tommaso, non è fine a se stesso, ma coinvolge chiunque nel ragionamento dell’autore. Si stava recando al Secondo Concilio di Lione, convocato da Gregorio X, quando la morte lo colse all’alba del 7 marzo 1274 nel monastero cistercense di Fossanova. Ciò non può essere avvenuto per cause naturali, considerando la sua giovane età di 48 anni. Contemplativo e devoto, fu amato da molti, ma non da tutti: quando Papa Giovanni XXII lo iscrisse nell’albo dei santi, parecchi obiettarono dicendo che Tommaso non aveva compiuto grandi prodigi né in vita né dopo la morte.

Ivan I di Russia

Fu un amministratore attento e uno stratega abile e assennato: durante la lunga guerra contro i Mongoli, difese egregiamente la città di Mosca e riuscì a porre fine allo scontro in maniera diplomatica. Ottenne, oltre alla carica di Principe di Mosca, anche quella di Principe di Vladimir. Iniziò, tuttavia, a sperperare ed accrescere, in via del tutto personale, le finanze del principato a cui era a capo, assumendo il ruolo di collettore dei tributi versati dall’Orda barbarica. A causa della sua smania di ricchezza, si guadagnò il soprannome di Kalita, cioè “borsello”. Nei suoi ultimi anni, Ivan si impegnò quasi esclusivamente nel prestito economico nei confronti dei principati confinanti, soggiogati dai debiti, che finirono per essere annessi al suo territorio. Forse furono proprio questi mezzi non del tutto limpidi a far desiderare la sua morte, avvenuta il 31 marzo 1340.

Pico della Mirandola

Umanista e filosofo, fu definito il più grande pensatore della cristianità dopo sant’Agostino. Purtroppo, la sua fama, dovuta anche alla straordinaria memoria, e l’ammirazione di Lorenzo il Magnifico non bastarono per far accettare le sue idee. Innocenzo VIII lo condannò per eresia e omosessualità, vietando lettura e stampa delle sue tesi. La condanna gli venne revocata solo molto tempo dopo da Papa Alessandro VI Borgia. Alcuni storici credono che Pico sia stato una delle prime vittime della grande epidemia di “mal francese” che colpì tutta l’Europa tra gli anni 1493 e 1494. Secondo gli antropologi, invece, sarebbe stato avvelenato e assassinato con l’arsenico, trovato in abbondanza nei suoi poveri resti.

Papa Alessandro VI Borgia

Si tratta probabilmente del Papa più controverso della storia cattolica. Di origine spagnola, battezzato Rodrigo Borgia, fu il protetto dello zio Papa Callisto III, che lo nominò cardinale all’età di 25 anni. Ebbe fin da giovane una condotta di vita dissoluta, infatti quando arrivò a Roma aveva già almeno un figlio illegittimo. Corrompendo un numero spropositato di cardinali, divenne Papa e continuò la sua vita licenziosa, non disdegnando né la simonia e né il nepotismo. Ebbe numerose amanti, di cui una fissa, Giovanna Cattanei, dalla quale ebbe addirittura quattro figli illegittimi. Morì il 18 agosto del 1503 a Roma, pare di avvelenamento per errore: si pensa che, durante un banchetto, abbia bevuto per sbaglio il veleno destinato ad un altro cardinale.

I Borgia sono storicamente noti per essere stati avvezzi all’uso del veleno con l’intento di eliminare avversari politici. La sorte di Papa Alessandro VI ci consente di capire come spesso i veleni possano torcersi contro le stesse persone più abili ad usarli.

Lucrezia Borgia, signora dei veleni.

Tra i quattro figli illegittimi che Rodrigo ebbe con Giovanna Cattanei, vi fu proprio Lucrezia: potente e colta, entrò nell’immaginario collettivo come la perfetta rappresentazione della donna bella e fatale e si fece largo nelle corti italiane per le sue spiccate abilità diplomatiche. A lei venne affidato il governo dello Stato della Chiesa nel 1501, mentre Papa Alessandro era in viaggio, e, in assenza dei consorti, nelle sue mani rimasero per lungo tempo anche i ducati di Pesaro e di Ferrara.

Di fatto, si sposò ben tre volte, sempre per volontà del padre o del fratello Cesare, e in funzione di contrarre alleanze vantaggiose. All’età di 13 anni, venne data in sposa a Giovanni Sforza, conte di Pesaro, la cui famiglia aveva sostenuto molto attivamente l’elezione di Alessandro. Il matrimonio venne però sciolto dallo stesso pontefice e Lucrezia sposò il duca Alfonso, figlio illegittimo del re di Napoli, da cui ebbe un figlio, Rodrigo. Nel frattempo, i francesi, alleati di Papa Alessandro, scesero in Italia, destando la preoccupazione del padre di Alfonso, che vedeva minacciato il suo regno. Il nuovo marito di Lucrezia divenne una figura pericolosa per i Borgia, viste le nuove tensioni tra le due famiglie, e venne ucciso da un gruppo di sicari. Infine, Lucrezia venne fatta sposare per la terza volta con Alfonso d’Este, duca di Ferrara.

A causa di questo suo, anche involontario, coinvolgimento negli intrighi orditi dalla sua famiglia, viene spesso associata a vicende oscure e immorali, di soprusi e omicidi. Durante tutto il pontificato di Alessandro VI, e per gran parte dei secoli successivi, l’immagine di Lucrezia subì numerosi attacchi. Secondo diverse leggende, si servì del veleno per eliminare nemici politici e amanti scomodi. Si diceva che possedesse un anello cavo, utilizzato per introdurre un veleno di sua invenzione: la sostanza, ottenuta grazie ad una particolare mistura di arsenico e viscere di maiale, una volta secca e ridotta in polvere, aveva una potenza tossica tale da uccidere, tra atroci tormenti, nel giro di ventiquattr’ore. Altri dicono che usasse far servire funghi tossici ai banchetti, che, grazie ad una azione ritardante, uccidevano gli sfortunati commensali a distanza di tempo, così da non destare sospetti. Infine, alcuni riportano che fosse solita impregnare di veleno le vesti dei propri amanti, in modo da ucciderli senza che nessuno potesse accorgersene.

Il 24 giugno del 1519 Lucrezia fu assalita da febbre e, sfinita dalle continue gravidanze, non riuscì a opporvi resistenza, morendo così a soli 39 anni.

Frank Cadogan Cowper – Ritratto di Lucrezia Borgia

POISONS IN THE ANCIENT WORLD

The short step from murderers to victims

Already used in Roman and Greek banquets, poisons were perfected in the use by the Islamic culture and in the Middle Ages they became great protagonists also between papal thrones. Accidents and murders started to be exchanged for indigestions or illnesses of dubious origin.

So, from ancient times, the same specific plants are used both for the production of medicines and terrible poisons. In fact, according to Paracelsus, “it’s the quantity that makes the poison”. Some plants are exotic species, but most are unsuspected examples that can easily grow in our gardens. An example is the oleander (Nerium oleander), a symbol of death in many cultures: every single part of it can cause nausea, vomit and impairments of cardiac rhythm. Five leaves, if ingested, are enough to kill. Other toxic plants which are simple to come across are the peony, which in the past was used to cause abortion, the lily of the valley, the hydrangea and the narcissus.

However, some examples are more reliable and lethal than others.

- Aconite (Aconitum napellus)

The aconitine, its active principle, is one of the most powerful poisons we know. It can easily be reduced in a white-yellow colored powder, it has a stinging taste and it is more soluble in alcohol than in water. The fatal dose for a man it’s 5 mg for Kg of body mass. Death occurs in a few hours, after violent cramps and a complete loss of consciousness. We do not know any antidote.

- Belladonna (Atropa belladonna)

This plant grows on stone walls and blooms in summer. All its parts are poisonous, but especially its sweetish berries. It has a particular influence on the brain and poisoning symptoms appear very soon. Death comes due to paralysis, generally after 24-36 hours from its ingestion.

- Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

It is a perennial plant with very big leaves and little white flowers. Its toxic essence is coniine, an oily, yellowish liquid with a piercing and unpleasant smell; little soluble in water but a lot in alcohol. The venom is paralyzing and death occurs due to asphyxiation after 3-6 hours from the intake.

- Mandragora (Mandragora officinarum)

Traditionally considered a creature between vegetable and animal kingdom, people thought that it could grow from the semen of men killed by hanging and that their crying could be lethal. Actually, its roots contain toxic alkaloids that, if taken in large quantities, can cause tachycardia, hallucinations, convulsions and death.

In Europe, during the Middle Ages and until mid XIX century, the most used toxic essences basically had a vegetable origin, but soon, when copper and lead acetates and mineral acids became more available, the knowledge was extended also to mineral origin essences. Different industrial factors made prevail now one and now one other poison.

- Arsenic

The substance is commonly used as poison is the arsenic trioxide, generally in mineral form. Also known as “the powder of heirs”, it is well soluble in water and has no scent and no flavour. This essence literally “burns” the intestine, causing death after a long pain.

- Cyanide

It is a salt extracted from Hydrogen cyanide. It stops the transport of oxygen to the cells, causing death by suffocation or a sudden loss of consciousness, with a consequent cardiac arrest. In most cases, a victim of cyanide poisoning has a typical scent of bitter almonds.

What makes these and other substances so famous are the occasions in which they were used: more known is the victim of a poison, more its fame increases. Therefore, it is appropriate to talk about the main deaths of which poisons can be responsible, at least it’s very probable they could. In fact, according to the sources we have, it is possible just to make guesse, since every death from poisoning is never certain.

In the case of hemlock, when we hear of this poison we immediately think about the great philosopher Socrates, who used that to take his own life, forced by the government of his own city, Athens. Plato, in the 66th chapter of the Phaedo, so tells the last moments of his master, after he drank the poison, and his death:

He walked about, until he said that his legs were getting heavy, and then he lay down on his back, as he was told. And the man who gave the poison began to examine his feet and leg from time to time. Then he pressed his foot hard and asked if there was any feeling in it, and Socrates said: «No»; and then his legs, and so higher and higher, and showed us that he was cold and stiff. And Socrates felt himself and said that when it came to his heart, he should be gone. He was already growing cold about the groin, when he uncovered his face, which had been covered, and spoke for the last time: «Crito» he said «I owe a cock to Asclepius; do not forget to pay it» […] After a short interval there was a movement, and the man uncovered him, and his eyes were fixed.

The offer of a cock was a traditional thank of those who healed from an illness to the god of medicine, Asclepius. The gift of the cock refers to a religious context: the best part of Socrates is not dead, but it resisted the challenge of individual historical existence and continues to live; for having assisted Socrates and his friends in the challenge, the god of medicine deserves a thank.

Thomas Aquinas

At the age of 18, against the will of his father and his brothers, he joined the order of the Preachers of St Dominic. He was a theologian, an intellectual, a philosophy professor and a writer. His most famous work is the Summa Theologiae, a script that, as every single one written by Thomas, is not an end in itself, but it involves everyone in the author’s reasoning. He was on his way to Lyon to attend the second council convened by Gregory X, when death caught him at the dawn of 7 march 1274 in the Cistercian Abbey of Fossanova. This fact could not happen from natural causes, considering he was just 48 years old. Contemplative and devoted, he was loved by many people, but not by all of them: when Pope John XXII fell him under him in the register of saints, many objected saying Thomas had never done any great prodigy, during his life or after his death.

Ivan I of Russia

He was a careful administrator and an able and wise strategist: during the great war against Mongols, he admirably defended the city of Moscow and managed to stop the feud using diplomacy. He obtained, in addition to the office of Prince of Moscow, the charge of Prince of Vladimir. However, he started to squander and increase, as he wished, the finances of his princedom, since the moment he became collector of tributes paid by the Barbarian Horde. Because of his desire about wealth, he gained the nickname Kalita, which means “wallet”. In his last years, Ivan was almost exclusively focused on lending money to the bordering princedoms, suffocated by debts that in the end fell under his power. Maybe these were not so clear manners to make others long for his death, which occured on 31 march 1340.

Pico della Mirandola

Humanist and philosopher, he was defined as the greatest thinker of Christianity after Saint Augustine. Unfortunately, his good fame, also due to his extraordinary memory, and the estimation of Lorenzo the Magnificent were not enough to make others accept his ideas. Innocent VII condemned him for being heretich and omosexual, forbidding reading and printing of his thesis. The conviction will be retired by Pope Alexander VI Borgia. Some historians believe Pico was one of the first victims of the great syphilis epidemic that hit all Europe between 1493 and 1494. Instead, according to anthropologists, he would have been poisoned and murdered by arsenic, which has been found galore in his miserable rests.

Pope Alexander VI Borgia

He was probably the most controversial Pope in Catholic history. Born in Spain and baptized Roderic Borgia, he was the protege of his uncle, Pope Callixtus III, who nominated him cardinal at the age of 25. Since his youth, he had always had a dissolute life: in fact, when he arrived in Rome, he had already had at least one illegitimate child. Corrupting a huge number of cardinals, he became Pope and continued his immoral life, not despising simony and nepotism. He had lots of lovers, one of which, Giovanna Cattanei, was permanent. From her, Alexander had four illegitimate sons. He died on 18 August 1503 in Rome, probably of a mistaken poisoning: it is believed that, during a banquet, he accidentally drank a poison which was destined to another cardinal.

Borgias are historically known because of their habit of killing political opponents with fatal essences. Pope Alexander’s story makes us understand how often venoms can harm the same people who are also the most able to use them.

Lucrezia Borgia, lady of poisons.

Lucrezia was one of the four illegitimate children that Giovanna Cattanei conceived with Alexander VI. Powerful and cultured and now seen as the perfect example of the woman both beautiful and lethal, she made her way in the Italian courts thanks to her strong diplomatic skills. In 1501, while Pope Alexander was missing, she ruled the State of the Church and, in absence of her husbands, she also governed the ducats of Pesaro and Ferrara for a long time.

In fact, she got married three times, following the will of her father or her brother, Cesare, and in order to get advantageous alliances. At the age of 13, she was forced to marry Giovanni Sforza, lord of Pesaro, whose family had actively supported Alexander’s election. However, the wedding was disbanded by the pontiff himself and Lucrezia married duke Alfonso, illegitimate son of the king of Naples, with whom she conceived a child, Roderic. In the meantime, the French went down to Italy causing the worry of Alfonso’s father, who feared for his kingdom. Lucrezia’s new husband became a dangerous figure for Borgias, since the new tensions between the two families, and he got killed by a group of hitmen. In the end, the girl got married for the third time with Alfonso d’Este, duke of Ferrara.

Because of her involvement in the family’s plot, even if it was unintentional, Lucrezia is often associated with murky and immoral matters, stories of abuses and murders. Under the pontificate of Alexander VI and for many centuries to come, her figure suffered several attacks. According to different legends, she would have used poison to eliminate political enemies and awkward lovers. People said she had a hollow ring used to introduce a poison invented by her. This substance was obtained by a particular mixture of arsenic and pork bowel and, after being dried and reduced to powder, it had such a strong poisonous power to kill a person in a matter of 24 hours, after excruciating torments. Other people said she was used to serving toxic mushrooms, mixed with a retardant compound, to her guests, in order to kill them one by one over time and without arousing suspicion. At last, some voices report she was used to soak her lover’s clothes with poison, to murder them without anyone noticing

On 24 june 1519, Lucrezia was assaulted by fever and, exhausted by the continuous pregnancies, she couldn’t stand up to it. She died at the age of 39.

Frank Cadogan Cowper – Picture of Lucrezia Borgia

ARTICOLO REDATTO DA NOEMI BILLIA DELLA CLASSE IIIA DEL LICEO CLASSICO

SITOGRAFIA:

https://www.focus.it/scienza/scienze/il-giardino-piu-velenoso-del-mondo

https://best5.it/post/i-veleni-nel-mondo-antico-il-metodo-piu-comune-per-eliminare-i-nemici/

http://best5.it/post/veleni-larte-di-uccidere-senza-sporcarsi-le-mani/

https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/veleni_%28Enciclopedia-Italiana%29/

https://biografieonline.it/morti.htm?causa=avvelenamento

http://www.enciclopediadelledonne.it/biografie/lucrezia-borgia/

BIBLIOGRAFIA:

“La biblioteca della natura: erbe” – Lesley Bremness

“Fedone” – Platone

“Veleni: farmaci o armi letali?” – Federica Baldi

Commenti recenti