|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

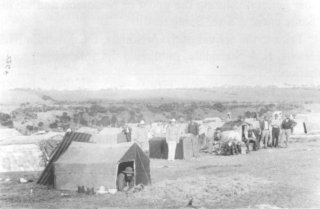

| Campo di concentramento sudafricano nella guerra anglo-boera |

- Winston Churchill, fatto prigioniero dai coloni, entra nel Parlamento inglese grazie alle battaglie combattute in Sudafrica

- Arthur Conan Doyle, medico negli ospedali da campo, diventa baronetto dopo aver appoggiato l’intervento inglese

- Robert Baden-Powell, fondatore del movimento degli scouts, diventa eroe nazionale soprattutto per aver resistito oltre sette mesi all’assedio della città di Mafeking da parte dei boeri. Proprio in quei mesi istruisce i bambini ed i ragazzi del luogo e li utilizza per alcuni compiti di guerra

I campi di concentramento britannici, arma del capitalismo internazionale mosso alla conquista delle Repubbliche boere, sterminarono circa il 50% della popolazione infantile boera. Venne invertita la natura delle cose, e madri e padri videro morire i loro figli. Effettivamente, il modo migliore per cancellare un volk è quello di farne morire i figli.

The Anglo Boer War (1899-1902) – Prisoners of War

This project is an extension of the The Anglo Boer War (1899-1902). The object of the project is to add information about both British/Colonial and Boer Prisoners of War, to gather profiles of these men who are on Geni and to share interesting tales and anecdotes about individuals.

The first sizable batch of Boer prisoners of war taken by the British consisted of those captured at the battle of Elandslaagte on 21 October 1899, which resulted in the capture of 188 Boer prisoners. No camps had been prepared and by arrangement with the Naval authorities these prisoners (approximately 200 men) were temporarily housed on the naval guard ship HMS Penelope in Simon’s Bay. Several ships were used as floating prisoner of war camps until permanent camps were established at Greenpoint, Cape Town and Bellevue, Simonstown. The first prisoners were accommodated in Bellevue on 28 February 1900. Wounded prisoners were sent to the old Cape Garrison Artillery Barracks at Simonstown which had been converted into the Palace hospital. The first wounded arrived on 2 November 1899.

Towards the end of 1900 with the first invasion of the Cape Colony the prisoners at Cape Town and Simonstown were placed on board ships. At the end of December 1900 some 2550 men were placed on board the Kildonan Castle where they remained for six weeks before they were removed to two other transports at Simons’ bay.

The camp at Ladysmith, Natal was in use from 20 December 1900 until January 1902. It was mainly used as a staging camp although it had some 120 prisoners of war. Another staging camp was also established at Umbilo in Natal.

As the number of prisoners grew, for example at Paardeberg, the decision was taken to hold the prisoners away from South Africa. Why overseas? There was nowhere that was suitable in South Africa. There was the problems of transport, the possibility that prisoners might be freed by their comrades and the burden of feeding the men. Of the 28,000 Boer men captured as prisoners of war, 25,630 were sent overseas. The approximate numbers of prisoners by camp was:

- St Helena – 5,000 (The first camp to be set up)

- Ceylon – 5,000 (Second location to be used for camps)

- Bermuda (The third location for camps)

- India

- Portugal – 1,443

- The total number of prisoners – 56,457

- Transvaal prisoners of war – 12,954

- Surrendered during the war – 13,780

- OFS prisoners of war – 12,358

- Surrendered during the war – 8,318

- Rebels convicted, awaiting trial and disposed of – 7,587

- Left Transvaal via Delagoa Bay – 400

- Left for German South West Africa – 200

- Made prisoners of war in error – 700

- Foreigners – prisoners of war – 160

When prisoners were taken, the British recorded full details under the following headings

- Prisoner Number

- Surname

- Christian names

- Nationality

- Age

- Home address

- Town or district

- Field Cornetcy or Commando

- Where captured

- Date of capture

- Date of receipt

Some of this information was published after the war.

The approximately 27,000 Boer prisoners and exiles in the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) were distributed far and wide throughout the world. They can be divided into three categories: prisoners of war, ‘undesirables’ and internees. Prisoners of war consisted exclusively of burghers captured while under arms. ‘Undesirables’ were men and women of the Cape Colony who sympathised with the Orange Free State and Transvaal Republics at war with Britain and who were therefore considered undesirable by the British. The internees were burghers and their families who had withdrawn across the frontier to Lourenço Marques at Komatipoort before the advancing British forces and had finally arrived in Portugal, where they were interned.

Prisoners of war were detained in South Africa in camps in Cape Town (Green Point) and at Simonstown (Bellevue), and some in prisons in the Cape Colony and Natal; in the Bermudas on Darrell’s, Tucker’s, Morgan’s, Burtt’s and Hawkins’ Islands; on St. Helena in the Broadbottom and Deadwood camps, and the recalcitrants in Fort Knoll; in India at Umballa, Amritsar, Sialkot, Bellary, Trichinopoly, Shahjahanpur, Ahmednagar, Kaity-Nilgris, Kakool and Bhim-Tal; and on Ceylon in Camp Diyatalawa and a few smaller camps at Ragama, Hambatota, Urugasmanhandiya and Mt. Lavinia (the hospital camp). The internees were kept in Portugal at Caldas da Rainha, Peniche and Alcobaqa. The ‘undesirables’, most of them from the Cape districts of Cradock, Middelburg, Graaf Reinet, Somerset East, Bedford and Aberdeen, were exiled to Port Alfred on the coast near Grahamstown.

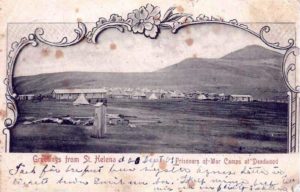

Boer prisoners of war on the Island of St Helena

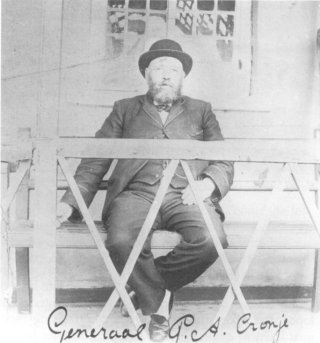

The Boer General Piet Cronjé was amongst the first contingent of 514 to arrive in St Helena on board the troop-ship Milwaukee, escorted by the HMS Niobe. On 27 February 1900, Cronjé had surrendered to Lord Roberts after the battle of Paardeberg. Illustrating his arrival on the island of St Helena, Punch magazine depicted the Boer general saluting the ghost of Napoleon and saying ‘Same enemy, Sire! Same result!’

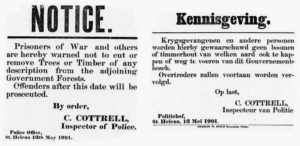

Prior to the arrival of the prisoners, the governor of St Helena, R A Sterndale, published the following proclamation:

- ‘.. His Excellency expresses the hope that the population will treat the prisoners of war with that courtesy and consideration which should be extended to all men who have fought bravely for what they considered the cause of their country, and will help in repressing any unseemly demonstrations which individuals might exhibit.’

Expecting harshness, rudeness and ill-feeling amongst the inhabitants, the prisoners discovered from the proclamation that they might anticipate courtesy and respect instead. Not a jeering sound nor rude remarks were heard from the crowd of islanders who had congregated to see them pass on their way to Deadwood Camp which had been prepared for them.

St Helena (Photo: A J Nathan)

General Cronjé and his wife, whom Lord Roberts had allowed to accompany her husband, were accommodated in ‘Kent Cottage’ instead of at the camp, but they were kept under a strong military guard which was changed every day. It is said that General Cronjé insisted that proper respect should be paid to his rank and that a mounted guard should be provided. As there were no mounted troops on the island, Govemor Sterndale, who always did his best to ease the lot of the prisoners, gave orders for some of the men of the St Helena Volunteers to receive riding lessons. As none of them had ever ridden before, or even been on a horse, it is not surprising that a few riding lessons did not transform them into proficient cavalrymen. As soon as they were able to sit in the saddle without losing their balance as they trotted or galloped, the troop was sent to ‘Kent Cottage’ to mount guard and to escort General Cronjé whenever he went riding. Immediately after his mounted guard arrived, General Cronjé decided to inspect the Boer prisoners’ camp at Deadwood Plain, some 10 km distant over hilly country. He led the way at a gallop with the guard following him. On arrival at the camp, the guard dismounted while the general made his inspection.

after the battle of Paardeberg.

(Photo: by courtesy of the Archives, Cape Town).

(Photo: by courtesy of the Archives, Cape Town).

When ready to return to ‘Kent Cottage’, General Cronjé remounted his horse and was ready to leave when an embarrassing situation arose. Not one of the guard was able to mount his horse whilst holding a rifle. To add to their humiliation, they had an audience of hundreds of Boers, most of whom were experienced riders. The comic opera developed a stage further when General Cronjé came to their rescue by ordering some of the prisoners to hold the guards’ rifles while they assisted them into the saddle. Amidst hearty cheers, the general left the camp followed by his mounted guard.

(Photos: by courtesy of the Archives, Cape Town).

There were a number of craftsmen amongst the prisoners at Deadwood Camp. On 10 May 1900, an exhibition was held over five days and model carts, carved boxes, pipes, walking sticks and so on, all made using makeshift tools (table knives serving as saws, umbrella wire as fret saws, stone hammers, etc) were displayed.

Considering the isolation of St Helena, surrounded by thousands of square kilometers of ocean, escape was virtually impossible. Yet, on 2 February 1901, four prisoners, including Commandant P Eloff, grandson of President Paul Kruger, made a determined attempt at Sandy Bay. Having collected a quantity of provisions, the four men seized an old fishing boat in which to make their escape. However, fishermen removed the oars and, despite a struggle, managed to hold on to them. The prisoners climbed into the boat and tore up the bottom boards, intending to use them as paddles. Finding them to be useless, the prisoners then returned to the beach and tried in vain to bribe the fishermen, offering them a good sum in exchange for the boat and oars. In the meantime, a messenger had been sent to report the occurrence and soon after dawn a guard arrived from Deadwood Camp to arrest the escapees.

Another escape was attempted by two Frenchmen amongst the prisoners. Whilst bathing off the beach at Rupert’s Bay, they tried to swim to a ship at anchor. Spotted by the guardship, guns were directed against them and they were challenged, whereupon one turned and swam back to Rupert’s Bay, whilst the other swam to the landing steps at Jamestown, only to be escorted back to camp.

(Photo: by courtesy of the Archives, Cape Town).

In 1901 there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in South Africa. All ships arriving at St Helena from the Cape were then under strict quarantine regulations. No passengers, other than those destined for the island, were allowed to disembark and no cargo was landed and there was no parcel post, all of which contributed to a serious loss of trade.

Despite the enormous odds against them, two prisoners could not resist another attempt at escape. Swimming from the wharf in Jamestown to a waterboat, the Phoebe, they set up sails and managed to slip away, unseen. The boat was not missed until the next morning and it was spotted from the signal station on Ladder Hill. The steamboat, the Beagle, was sent to retrieve it. Brought before the magistrate, one of the prisoners declared that he had had no intention of stealing the boat but had merely wanted to get away from the island! He was fined £5, which was paid by his fellow prisoners, and sent back to camp.

The Boer camp at Deadwood Plain was surrounded by three separate barbed wire fences and guarded outside by patrolling soldiers. By and large, there was little trouble but as in most communities where men are closely confined there were bound to be some agitators. Usually the prisoners would settle their differences amongst themselves but occasionally cases were reported to the British commandant and then the ring leaders would be confined for a time at High Knoll, a large fort isolated on a hill top.

It was inevitable that there were occasional spots of serious trouble. For example, on one Saturday night early in 1901 a prisoner was shot by a sentry. It emerged at the Military Court which followed that for some time the prisoners had been pelting the sentries with stones, sticks, tin cans and other missiles, and that the sentry in question had been struck in the face on that occasion.

Tired of sharing tents, some of the prisoners saved some money and constructed cosy little huts out of paraffin tins soldered together and lined with wood or cloth. The commandants were allowed to live outside the camp in comparative freedom, with few restrictions being placed on their movements.

In 1902, there was a serious outbreak of enteric fever in the camp, the cause of which remains rather obscure. Since the water supply was not found to be at fault, it was concluded that the disease had been brought to the island by the last contingent of prisoners to arrive. A number of nurses and additional medical aid were brought in and the fever, which caused numerous deaths, gradually declined.

As time passed, many prisoners gave their names to the British commandant, indicating that they were in favour of peace. This caused such bitterness amongst those loyal to the Boer cause that the authorities were compelled to form another camp. called Peace Camp or No 2. Later, General Cronjé himself went to the Castle and took the oath of allegiance. His guard remained with him at his request, as many of the prisoners were resentful towards him. He finally left St Helena for the Cape on 22 August 1902 with 994 other prisoners in the transport Tagus.

Many incidents reflected the general good feelings which existed amongst the prisoners, the local population and the military staff. A typical example of this was the following address presented by the German prisoners of war to the governor before leaving the island:

-

- ‘Your Excellency,

-

- Having heard that peace has been proclaimed and the POWs are soon to leave the island, the undersigned take the liberty of addressing Your Excellency.

In the first place we want to express our heartfelt thanks for the kindness and consideration shown to the POWs. The kindness shown to one and all by all the people of the island, with a few exceptions, is a fact that will be long remembered and cherished by them as a bright spark in the gloomy days of captivity at St Helena.’

(Photos: A J Nathan).

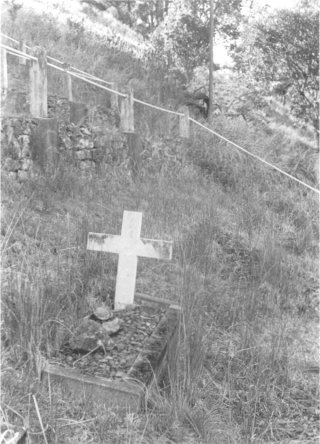

The Boer cemetery is in a wooded and most attractive part of the island, but on extremely steep ground. In 1913, the Union Government sent over two granite monuments which were erected at the bottom of the slope containing the graves. On them are inscribed the names of all who died, including their ages, which ranged from sixteen to sixty-one.

names and ages of those who died on the island

(Photo: A J Nathan).

Bibliography

Jackson, E L, St Helena (Ward, Lock, 1903).

Gosse, P, St Helena, 1502-1938 (Cassell & Co.)

St Helena Guardian. 12 and 19 April 1900, 17 May 1900, February 1901, 20 May 1901, 4 July 1901, 15 August 1901, 8 May 1902, and 10 July 1902.

Commenti recenti