CONSULTA LINK

http://www.storiologia.it/seppinnerkofler.htm

The people of the valley heard the shooting and prayed for the soldiers fighting up there, without making any distinction between Italian and Austrian.

The History of Val Vanoi

On the fourth of July 1915, an Austrian soldier died on a remote mountaintop in the Dolomites. In the history of the Alpine front, where Italy and Austria battled for three terrible years, two men stand as symbols of each nation’s passion and pathos: Caesare Battisti, patriot of Italy and the Trentino who was executed by the Austrians, and Sepp Innerkofler, the Tyrolean mountaineer, who died defending his homeland on that July Day. Innerkofler, father and noted mountain guide, had taken up arms to fight what he perceived as interlopers and enemies, his Italian neighbors who had once waved at him from nearby peaks, or shared a smoke in the climbing hutte on summer evenings.

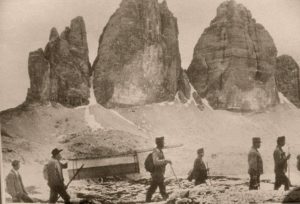

Monte Paterno [Left], Drei Zinnen [Right]

Note Destroyed Dreizinnenhutte on Far Right

Sepp’s world centered on the Drei Zinnen [or Tre Cime di Lavaredo] peaks of the eastern or Sextener Dolomites. The three summits are amongst the most recognizable and spectacular sights and climbs to be found in the Alps. The Innerkofler family had farmed the area for generations before Sepp was born there on the 28th of October, 1865, the fourth son of Christian Innerkofler, a yeoman farmer and stonecutter.

Innerkofler’s two life pursuits would result from his uncles’ influence. Hans, nick-named Der Gamsmannchen or the Chamois Man, introduced Sepp to hunting. As a lad, Sepp learned to supplement the family table with small game such as mountain grouse; under Hans’s tutelage his quarry eventually became the ibex and chamois, the ultimate game on mountain and cliff. Several of his family had also been mountaineering guides, including his other uncle Michel. Known as the Dolomitenkonig [King of the Dolomites], Michel’s exploits were legendary. Tragically, he was killed climbing Monte Cristallo in 1888, when a glacier’s snow bridge collapsed. Innerkofler would gain renown by expanding on Michel’s early instructions, putting up over fifty first ascents in many of the area’s classic climbing areas, as well as climbing in the Dachstein Range to the north and on the mighty Matterhorn/Cervino in Zermatt, Switzerland. Sepp’s prowess in the combined skills soon became second to none.

By the end of the 19th century, as the European middle class grew in size and adventurous spirit, mountaineering was becoming a popular summer pastime and athletic pursuit. Guides were needed for bourgeoisie climbers, to give advanced lessons and for path finding up the soaring cliffs. Sepp Innerkofler found his calling in this trade and excelled at it. In 1890 Sepp was certified as a mountain guide, no small event in Sexten. He earned 200 florins his first summer guiding; the following seasons brought double that amount.. Most climbing in the Alps, or any peaks a century ago, was on glaciers, with the occasional rock obstacle. A guide cut steps into the ice and kept a course for the summit. There is less ice in the Eastern Alps, but an abundance of vertical rock. New techniques and equipment had to be developed for the extended rock crack, chimney, overhang and knife-edge ridge. Sepp himself was a pioneer of vertical rock climbing for which the Dolomites are now renowned.

After five years of guiding, Sepp married the love of his life, Maria Stadler, in the off-season, January 8th, 1895. Their marriage was blessed with five children — Gottfried [b.1896] Josef [b.1898] Franz [b.1900] Maria [b.1902] and Adelheid [b.1904]. Sepp insured security and comfort for his wife and children by working at the local saw mill in the winter and by investing. Sepp and Maria managed the climbers’ refuge at Monte Elmo for several seasons. In 1898, they opened their own Dreizinnenhutte, a stone chalet comfortable enough for middle-class tourists from Vienna or Venice and rugged enough to withstand mountain wind, snow, and cold. Clients could relax at dinner, basking in Tyrolian hospitality and the glorious sight of peaks that only hours earlier they had stood atop. In 1903 the Innerkofler’s income increased when they opened the Hotel Dolomiten in Val Fiscalina. For love of family and mountains, the poor son of a peasant stonecutter and farmer had become one of Europe’s eminent climbing guides and a man of property.

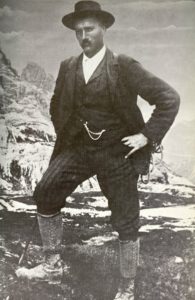

1890 Sepp [Center] is Certified with Four Others as Professional Mountain Guides by Austrian Government

Sepp Innerkofler was also a member of the Third Company of the Austrian Standschutzen, the alpine militia based in Sexten. With their symbolic edelweiss badge and spielhahnstoss [black mountain grouse feather] in their caps, the Standschutzen were government subsidized rifle clubs made up of those too young [14 to 20 years old] or too old [40 to 70] for active duty. Defense of their alpine province was the sole mission of these reservists. A similar group, the Landesschutzen, were reservists of military age [21 to 41], but liable to service outside the region. Both groups, at least in the Tyrol, were expert riflemen, considering the necessity of hunting combined with a regional pride in shooting. [Imagine men from Siberia, Afghanistan or Montana.] Indeed, out of necessity, mountain people across Europe have been allowed a much greater liberty with firearms due to their remoteness and fierceness. Rather than costly police actions, most rulers found it easier to allow shooting clubs and patriotic militias to pacify their own mountain areas.

The Standschutzen, were made up of men who had spent their lives in the mountains: climbing guides and porters, herders and foresters, some even possessing the unique skills of poachers and smugglers. Sepp Innerkofler, with his obvious talents and strong personality, was elected Zugsfuhrer [section or platoon sergeant] of a “flying patrol” of twelve of the best on high rock. His region was also manned by the elite Kaiserjager alpine troops, the “Imperials” of the regular Austro-Hungarian Army, as well as a regiment of the German Army Alpenkorps. When the war began in 1914, Austria’s military situation on the Eastern Front soon became critical. All regular army and most Landesschutzen units were sent to face the Russians. The Tyrolean Dolomites were left in the hands of the teenagers and old men of the Standschutzen.

Two of Sepp’s Sons Served with Him Gottfried [Sitting] and Josef |

Spring 1915 saw the Italian army invading the Tyrol which they claimed as theirs. Alpini units, mountain troops par excellence, professional and elite, recruited from their alpine peoples and climbers, raced Standschutzen patrols to occupy the highest points along the front after the opening shots of 24/25 May. Italy hoped to catch Austria, with most of their forces in Russia, off guard.

A week later Sepp Innerkofler would see his first action, occupying the summit of the icy Cima Undici/Elferkofel [3092m.] and repelling an observation party of Italian climbers only moments behind them. He would participate in 17 patrols and firefights between the end of May and the 4th of July in 1915 and was awarded the Silver Medal of Valor [second class] for his leadership and bravery. The Standschutzen had two advantages, despite being outgunned and outnumbered. For the most part, they controlled the high ground and were often fighting around the same valley where they lived. The front line went directly through Sepp’s beloved Drei Zinnen refuge which was totally destroyed by Italian artillery fire the first days of the war. No doubt Sepp had carefully observed Italian positions from the ruined shell of the house that Maria and he had built. What thoughts went through his head? Even in battle Innerkofler was known for being calm, not vindictive or hateful. Nor was his patriotism rabid. But these were his people’s mountains. By the end of May, Monte Paterno/Paternkofel [2746m.] and nearby Tre Cime de Laveredo/Drei Zinnen [2999m.] had become Italian strongholds, with their cannon and machineguns creating a deadly crossfire.

On the 18th of June 1915 Innerkofler earned a second Silver Medal [1st class] for retaining his lofty observation post on Cima Uno/Einserkofel [2699m.] after “a violent duel with the Alpini.” His son Gottfried fought by his side on the summit from which they could observe Sexten and the family home. The following morning Sepp reported an estimated 450 Alpini and their artillery reoccupying the strategic summit of Cima Undici that overlooked Passo Monte Croce Comelico [1636m.] and the road to Sexten, Brunico and the Brenner Pass. During an interlude, men from both sides silently observed Innerkofler stalking a solitary chamois buck. The foreboding and emotions felt by the both the Alpini and Austrians watching can only be imagined as Sepp’s rifle brought the animal down in a dramatic scene of death in the high mountains. It was, however, to be his final hunt.

In the Tre Cime area, any successful Austrian defense or attack would require the Alpini outpost atop Monte Paterno to be eliminated. Only one man in the Emperor’s army was capable of such an undertaking, in regards to climbing skill and knowledge of the spire itself. Sepp Innerkofler was assigned to lead the best five men of his flying patrol against the lofty stronghold. An entire platoon of Austrians followed prepared to hold the vital observation post once it was secured. Nearby mountain howitzer batteries were prepared to give suppressive fire, as was every Austrian machinegun position in the saddle between summits. As with Innerkofler’s chamois hunt, the battle would be witnessed by thousands.

The following are eyewitness accounts of what must be one of the most dramatic duels of the Great War. The first is by Antonio Berti, an Alpini medical officer from the Pieve di Cadore battalion from his book Guerra in Ampezzo e Cadore, written in 1967.

There are six, all volunteers, of which three are over fifty years of age, renowned guides in the Val di Sesto- Sepp Innerkofler, Hans Forcher, Andreas Piller. [With them as well are the other younger men in their famous squad- von Rapp, Taibon and Rogger]. They have received the order to climb the Paterno and occupy its top. Armed with carbines and hand grenades, they leave barracks near the Drezinnenhutte, devastated by fire. With them is a platoon consisting of thirty Landesschutzen and a few military engineers commanded by Christl, Sepp’s brother. They set out on a gravel path descending from the Sella del Camoscio, and proceed slowly and stealthily, being careful not to displace any stone that might arouse the enemy’s suspicion. Christl and his platoon stop at the top of the path, waiting for events to start happening. The six put on their climbing shoes and start up the wall of the Paterno.

Sepp Innerkofler [Center] and His Flying PatrolWith complete assurance they climb under cover of darkness; the way is known as the NNW passage, the same one Sepp was the first man to ascend in 1896, and has climbed countless times since. One hour later the six reach the top [crest] in the dim light of dawn. From Monte Rudo the Austrians start to shoot at once. Then twice again the roar and hiss of the cannons are heard from a lower altitude; a fourth roar brings down a hail of shattered rocks- then a silence. The six men keep on climbing in single file along the edge of the peak. From Forcella di Pian di Cengia, the Alpini can clearly see them silhouetted against the red sky. That is the awaited signal, and while the six climb toward the west [with the sun to their backs], the Italians open fire from [Tre Cime di] Lavaredo. Immediately the Austrians respond, bringing their own machineguns into action. Over the roar one can hear the Austrian cannons on Monte Rudo and a mortar from Sasso di Sesto. A 105 howitzer shoots without letup, toward the Forcella di Pian di Cenega, from the [Austrian] Torre dei Scarperi. The six continue climbing, cautiously, in short sprints, hiding in every hollow. An artillery fragment hits Sepp in the forehead. Blood streaks down his face and covers his eyes; yet he continues to climb. A rock splinter hits Forcher is also on the forehead; he bleeds, but continues to climb. They have almost reached the top. Suddenly, as if by a pre-arranged signal, an eerie quiet succeeds the thunder. A silence of death spreads through the valley, over the mountaintops, on all sides of the trenches. At this precise moment, slowly and clearly visible, one man alone begins to ascend. Ten steps below the top Innerkofler crosses himself and with a wide arc hurls a grenade over the wall of the summit outpost. He then throws a second and a third. Suddenly, an Alpini soldier appears, his face bleeding from the effects of the first grenade. Shouting “So! You won’t go away?” [meaning, “I am going to get you.”] Standing above the wall, he holds a rock high over his head. He throws it, and Sepp is fatally hit. Raising his arms toward the sky, he falls backward and plummets [50 meters] into a narrow mountain chimney, dead. The Alpini who hurled the rock is Pietro de Luca, an engineer of the Pieve di Cadore Battalion. |

A second, lesser known memoir of the battle gives an account quite different from Berti’s. Speaking is Pietro de Luca himself to a Captain Neri in the book Inediti di Guerra Alpina, 1915-1918 [Edited by Marino and Francesca Michieli in 1996]. De Luca was part of a group of six alpini of the Val Piave Battalion led by Corporal Da Rin posted the Monte Paterno. This is his reconstruction of what happened:

Once in a while I had to look up from below, as I was ordered to do. [De Luca was on sentry duty below the summit ridge.] There was not a living soul! But it was hard to say as it was dark as hell. I had just looked around and then headed behind the cover of a rock, as ordered by Da Rin, since dawn was approaching. It was then that I saw a shadow. Could it be the devil? I said to myself, “Devil my eye!” There was a man all right! The shadow had its back to me and moved as if it was pulling a bucket from a well. I understood afterwards that it was trying to help others climb.

Alpini Squad that Occupied Monte Paterno in 1915Blessed Virgin Mary! That can only be the enemy, I said to myself and I jumped him. Hell, he was strong like a demon, so much so I was not sure that I could take him! I managed to throw him off and as he came at me again I picked up a rock and crushed his face, sending him straight over the cliff faster than I could say amen. [This entire struggle took place on a ledge or ‘shelf’ twenty feet long and one or two feet wide, with sheer cliffs above and below.] I forced myself to look down, so I could check where he fell and…damn, what did I see! Just below me there were about thirty of those “mamaluchi” [Mamelukes- an Italian pejorative] climbing like ants. “Da Rin! Da Rin”! I started to yell out. But I could not waste time waiting for Da Rin; so I started to push rock after rock down. It was a pleasure to see them roll down and hear them curse words I could not understand one damn bit… |

The Italian squad atop Paterno was quick to respond with a shower of grenades and rifle fire. A call for artillery and mortar fire soon arrived. The Austrians fled. Later that day, under continued rifle and machinegun fire, Innerkofler’s body would be found and examined by an Alpini medic, Angelo Loschi. The men atop Monte Paterno reverently buried Sepp on a wide part of the summit ridge on his beloved Paternkofel, beneath a simple cross inscribed “Sepp Innerkofler, guida.” When news of this battle reached the Austrian high command Innerkofler was posthumously awarded the Gold Medal for bravery. Of the eight million subjects who served, only 3,700 were awarded this highest of honors.

Sepp’s Grave on Monte Paterno

Battles continued to rage on summit and plateau each short summer, yet their intensity diminished as units from both sides were siphoned off to Russia or the Isonzo River Front. On the morning of November 1st 1917, the Austrian forces realized the Italians had abandoned their positions in a front wide retreat after the Battle of Caporetto. The Italians had lost a quarter of a million men there, and were now incapable of holding a vast high altitude front. The area around Monte Paterno and the Tre Cime returned to nature’s silence.

In August of 1918 a small expedition was sent to exhume Sepp Innerkofler’s remains. This climb in itself was no minor feat. He was returned to his family in Sexten, and buried in the community cemetery along side parents, uncles and eventually 54 other men from Sexten who died in the war. One million Austrian and Italian men would die on the alpine front in avalanche, lightning strike or blizzard or from poison gas, artillery and machinegun. Sepp’s sons Gottfried and Josef had enlisted, fought and survived this enormous war. Josef would live until 1993, and the great age of 97 years. Sepp’s memory lives on in his many grandchildren and their thriving families, the rebuilt Drei Zinnen Hutte and the eternal Dolomites. Mutual understanding increases in this bicultural area with each generation — a type of tolerance quite different from events only one hundred miles to the east in the former Yugoslavia, where mountain warfare has not ceased. The memory of Sepp Innerkofler is now honored all its citizens.

Sources and Thanks: I would like to send my deepest appreciation and thanks to the Innerkofler family of Sexten for all the information and depth regarding their ancestors and area. I would also like to thank my friend Salvatore Vasta, editor of Coorte military history magazine, for his assistance in translating the Fruilian dialect. Postcards and photos are from the authors personal collections and the outstanding three volume history by Hans Von Leichem, Gebirgskreig 1915-1918.

Ultimo di quattro fratelli, nasce a Sesto nel 1865 da una famiglia che aveva fatto dell’alpinismo una tradizione. Tutto era iniziato con il capostipite Josef (1802-1887) il quale si dedicò con successo a diverse ascensioni, seppure con tutte le limitazioni imposte dai materiali del tempo.

Il figlio Josef (1842-1919) fu la prima guida alpina patentata e diversi membri della famiglia compirono una lunga serie di prime ascensioni sulle Dolomiti, come Jakob (1833-1895) e Michael (1844-1888) che conquistarono la Cima Dodici, la Cima Piccola di Lavaredo, la Cima Undici ed il Cadin della Neve

Sepp, destinato dal padre Cristian ad intraprendere il mestiere di scalpellino, lavorò per diversi anni in una segheria di Sesto dedicando però ogni minuto libero all’arrampicata ed alla caccia finché, nel 1889, conseguì la patente di guida alpina.

Da quel momento in poi l’attività di guida divenne sempre più importante e remunerativa consentendogli di sposarsi e di mantenere sette figli.

Dopo la scalata della parete nord della Cima Piccola di Lavaredo, fino ad allora ritenuta impossibile, la sua fama crebbe a dismisura, tanto che divenne la guida più ricercata della zona, con clienti che aspettavano giorni e giorni pur di avere il privilegio di farsi guidare da Sepp.

Dal 1895, assieme alla moglie, gestì il rifugio su monte Elmo e poi dal 1898 fino alla distruzione -avvenuta nel 1915 – il rifugio Dreizinnen (Tre Cime) ora Rif. Locatelli.

I proventi derivati dalla gestione dei rifugi e dall’attività di guida gli consentirono di costruire la villa Innerkofler a Sesto come dimora di famiglia ed in seguito l’albergo Dolomiten in val Fiscalina, dotando quest’ultimo di tutte le comodità disponibili al tempo, compresa la luce elettrica che otteneva da un generatore autonomo.

Il povero figlio di scalpellino si trasformò quindi nella persona più ricca e conosciuta della valle ed in una delle guide più stimate dagli alpinisti di tutta Europa.

Lo scoppio della guerra mise fine al periodo d’oro dell’alpinismo e la mobilitazione generale del 1914 rese nuovamente le Dolomiti il regno del silenzio.

Le guide alpine trascorrevano le loro giornate nei rifugi interrogandosi sulla loro sorte e quelli come Sepp, che non erano stati richiamati dalla leva, passarono l’inverno del 1914 in relativa tranquillità anche se le notizie dal fronte russo e le prime liste dei morti della valle non erano certo confortanti.

Nella primavera del 1915 gli strani movimenti a sud del confine e l’accumulo di truppe alpine italiane convinsero i valligiani che era finito il periodo di pace nella loro terra.

Allo scoppio delle ostilità con l’Italia, nel maggio del 1915, il Comando di difesa del Tirolo lavorò febbrilmente per costruire una parvenza di fronte, completamente sguarnito sia dal punto di vista delle truppe (tutti gli arruolati validi erano dislocati sul fronte russo) che dei mezzi. Fu presa quindi la decisione di arretrare la linea difensiva di qualche chilometro, abbandonando diverse località (fra le quali Cortina d’Ampezzo), ma riducendo il fronte a meno di 350 Km.

Il grosso problema era costituito dalla mancanza cronica di truppe: quelle disponibili consistevano in 17.000 territoriali di basso valore militare (più che altro guardie di confine dedite al controllo dei contrabbandieri e corpi di polizia locali) che non avrebbero avuto alcuna possibilità di resistere ad un assalto italiano.

Il 18 maggio l’imperatore ordinò la mobilitazione generale degli standshützen (costituiti da iscritti ai poligoni di tiro, cacciatori e volontari) ottenendo così un corpo di 38.000 arruolati fra i 14 ed i 70 anni di età.

Di questi, solo 18.000 vennero impiegati in prima linea, consentendo una certa copertura del fronte sebbene con l’impiego di elementi privi di preparazione militare.

Anche Sepp, assieme al figlio Gottfried e ai fratelli, si era arruolato fra i volontari e si trovò a combattere nel punto cardine del sistema difensivo tirolese comprendente il passo Croce e la valle di Landro, punti di accesso verso nord dotati di strade moderne e distanti appena 15 Km dalla linea ferroviaria della Pusteria.

Lo sfondamento da parte degli italiani di questi punti di passaggio sarebbe stato difficilmente arginabile, e avrebbe consentito alle truppe alpine di interrompere i rifornimenti austriaci, raggiungere il Brennero e conquistare Vienna senza trovare alcuna resistenza.

L’ordine era quindi di resistere ad ogni costo con le forze disponibili lungo la linea di cresta delle montagne in modo da rendere più difendibile il fronte.

Vennero costituite delle pattuglie di ricognizione: fra queste anche quella di Sepp, che comprendeva, oltre al figlio, altre guide della zona. La pattuglia cominciò la sua attività bellica il 21 maggio con la scalata del Paterno.

Fra il 21 maggio ed il 4 luglio (giorno della sua morte), Sepp effettuò ben 17 giri di pattuglia ottenendo per lui e per la sua squadra promozioni e decorazioni (divenne caporale e subito sergente maggiore saltando ben due gradi della gerarchia militare) cosa resa ancor più singolare e meritoria dal fatto che, essendo uno standshütze, non era un militare a tutti gli effetti.

Dal suo diario, tenuto fra il 19 maggio ed il 3 luglio, si ricavano le imprese svolte dalla pattuglia durante quei giorni.

Il tono è sobrio e non vi è cenno di retorica o di critica nei confronti dell’una o dell’altra parte; vengono annotate le imprese con commenti anche di natura tecnica e sportiva, quasi fossero degli appunti di escursioni effettuate accompagnando i turisti.

Ovviamente nel diario sono anche contenute indicazioni di natura militare legate alla situazione meteorologica, alle manovre italiane ed austriache, alle valutazioni di tiro per l’artiglieria, ma si capisce bene quale genere di rapporto legasse questi uomini alla montagna.

Nelle annotazioni del suo diario se ne trova perfino una del 25 maggio, incredibilmente flemmatica, dove assiste alla distruzione del suo rifugio per opera dell’artiglieria italiana.

Per Sepp il Paterno e l’altopiano delle Tre Cime rappresentavano i punti di forza per la linea difensiva sopra la valle di Landro. Riuscì perciò a convincere il comando di zona a farsi assegnare l’occupazione (almeno durante la giornata) della cima del Paterno.

Il 29 maggio la conquista definitiva da parte italiana della cima (a causa delle condizioni meteorologiche avverse che favorirono gli alpini), costrinse gli austriaci ad una serie di assalti per riconquistare quanto perduto.

Da momento che la cima del Paterno misura pochi metri quadrati, il solo modo per riconquistarla era la scalata della montagna da parte di un piccolo gruppo di uomini in modo da sorprendere gli italiani, attestati dietro un muretto lungo poco più di tre metri e alto appena 80 centimetri.

L’unica cordata in grado di compiere questa impresa era la “Pattuglia” di Sepp che difatti cominciò la scalata all’una di notte del 4 luglio.

Giunti in cima furono però scoperti dalla difesa italiana che cercò di respingerli sia con i fucili che con tiro di pietre.

Qui finisce la narrazione storica ed inizia la leggenda in quanto vi sono tre versioni completamente diverse della morte di Sepp.

Nella prima Sepp si erge dietro un sasso, lancia tre o quattro bombe a mano, delle quali forse solo una esplode, e poi viene visto dai suoi compagni “colpito alla fronte precipitare con un urlo giù per la parete e cadere sulla ghiaia.”(1)

La seconda, di parte italiana, cita : “D’improvviso appare, dritta sul muretto della vedetta della cima, la figura di un soldato alpino – Pietro De Luca del battaglione Val Piave – campeggiante nel tersissimo cielo, alte le mani armate di un sasso, rigata la fronte di rosso della prima bomba. «Ah! No te vol andar via?». Prende giusto la mira, scaglia con le due mani il sasso! Il Sepp alza le braccia al cielo, cade riverso, piomba, si incastra nel camino Oppel, morto.” (2)

La terza versione, che serpeggia fra i compagni di Sepp ed i valligiani, è invece che siano stati gli stessi austriaci ad ucciderlo per errore proprio nel momento in cui si era alzato per snidare la vedetta italiana e che ben si evidenzia in quanto scritto nel 1937 e poi nel 1975 dal figlio Sepp jr.

“… mio padre si mise a maneggiare il fucile e nello stesso tempo la mitragliatrice sulla Torre di Toblin (cioè austriaca) iniziò a sparare. Venne subito messa a tacere, ma era già troppo tardi, perché all’istante vidi mio padre scivolare giù per la parete e giacere presso il camino Oppel. Alla esumazione sul Paterno (agosto 1818) non ero presente. Alla seconda esumazione nel camposanto di Sesto ero presente e vidi come la testa fosse perforata diagonalmente dalla fronte verso l’occipite. M’immagino che mio padre si accorse che gli sparavano addosso da dietro e che si voltò. Infatti ho esattamente accertato che l’uscita della pallottola avvenne da dietro.”(3)

Queste in sintesi le tre versioni più diffuse sulla sua morte alle quali vanno aggiunte le oltre trenta ricostruzioni ed interpretazioni che si sono sommate nel tempo attraverso comunicati ufficiali ed articoli di giornale che alimentarono, assieme alla fama di Sepp alpinista, la leggenda dell’uomo che presto accomunò italiani, austriaci e tedeschi sia durante che dopo la guerra.

Il 9 luglio l’arciduca Eugenio d’Asburgo conferì a Sepp la medaglia d’oro al valor militare.

Gli alpini italiani recuperarono la salma nonostante il tiro nemico per poterla seppellire, come sommo gesto di stima, sulla cima del Paterno per la quale e sulla quale egli era morto.

Note :

(1)-(3) Viktor Shemfil, Opere varie citate da Cristoph von Hartungen in Aquile in guerra

(2) A.Berti, 1915-1917. Guerra in Ampezzo e Cadore.

Commenti recenti