CONSULTA LINK

https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/gramophone/028011-3001-e.html

http://anzacsightsound.org/collections/popular-music-during-the-war

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01n4mxk

World War I (WWI or WW1 or World War One), also known as the First World War or the Great War, was a global war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918.

More than 9 million combatants and 7 million civilians died as a result of the war, a casualty rate exacerbated by the belligerents’ technological and industrial sophistication, and tactical stalemate. It was one of the deadliest conflicts in history, paving the way for major political changes, including revolutions in many of the nations involved. The war drew in all the world’s economic great powers, which were assembled in two opposing alliances: the Allies (based on the Triple Entente of the United Kingdom, France and the Russian Empire) and the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary. Although Italy had also been a member of the Triple Alliance alongside Germany and Austria-Hungary, it did not join the Central Powers, as Austria-Hungary had taken the offensive against the terms of the alliance.

These alliances were reorganised and expanded as more nations entered the war: Italy, Japan and the United States joined the Allies, and the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria the Central Powers. Ultimately, more than 70 million military personnel, including 60 million Europeans, were mobilised in one of the largest wars in history. The immediate trigger for war was the 28 June 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, by Yugoslav nationalist Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo.

This set off a diplomatic crisis when Austria-Hungary delivered an ultimatum to the Kingdom of Serbia, and international alliances formed over the previous decades were invoked. Within weeks, the major powers were at war and the conflict soon spread around the world. On 28 July, the Austro-Hungarians fired the first shots in preparation for the invasion of Serbia. As Russia mobilised, Germany invaded neutral Belgium and Luxembourg before moving towards France, leading Britain to declare war on Germany. After the German march on Paris was halted, what became known as the Western Front settled into a battle of attrition, with a trench line that would change little until 1917.

Meanwhile, on the Eastern Front, the Russian army was successful against the Austro-Hungarians, but was stopped in its invasion of East Prussia by the Germans. In November 1914, the Ottoman Empire joined the war, opening fronts in the Caucasus, Mesopotamia and the Sinai. Italy and Bulgaria went to war in 1915, Romania in 1916, and the United States in 1917. The war approached a resolution after the Russian government collapsed in March 1917, and a subsequent revolution in November brought the Russians to terms with the Central Powers. On 4 November 1918, the Austro-Hungarian empire agreed to an armistice. After a 1918 German offensive along the western front, the Allies drove back the Germans in a series of successful offensives and began entering the trenches. Germany, which had its own trouble with revolutionaries, agreed to an armistice on 11 November 1918, ending the war in victory for the Allies. By the end of the war, four major imperial powers—the German, Russian, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires—ceased to exist.

The successor states of the former two lost substantial territory, while the latter two were dismantled. The maps of Europe and Southwest Asia were redrawn, with several independent nations restored or created. The League of Nations was formed with the aim of preventing any repetition of such an appalling conflict. This aim, however, failed with weakened states, renewed European nationalism and the German feeling of humiliation contributing to the rise of fascism. All of these conditions eventually led to World War II.

1. Pack Up Your Troubles – Murray Johnson

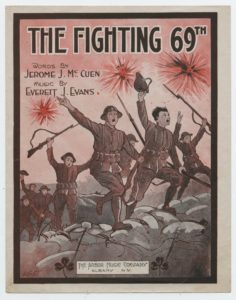

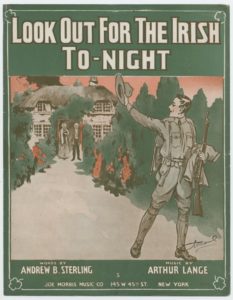

The Irish in World War I Songs

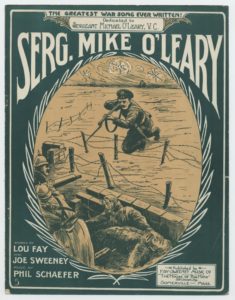

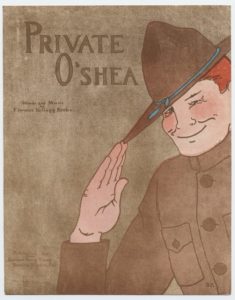

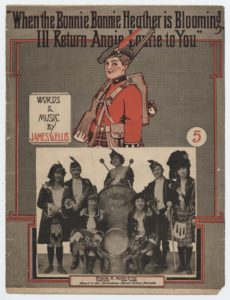

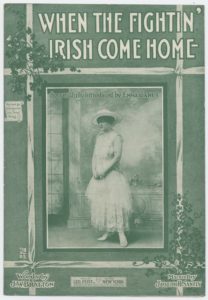

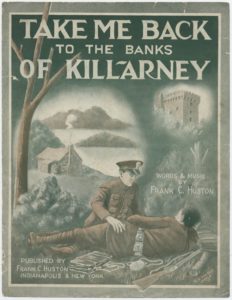

The Irish experience during World War I (1914-1918) was complex, and the variety of Irish and Irish American themes in popular sheet music of the era reflects this complexity. These themes include romantic songs, songs honoring military units, patriotic songs, and songs reflecting Irish politics of the time.

The Irish experience during World War I (1914-1918) was complex, and the variety of Irish and Irish American themes in popular sheet music of the era reflects this complexity. These themes include romantic songs, songs honoring military units, patriotic songs, and songs reflecting Irish politics of the time.

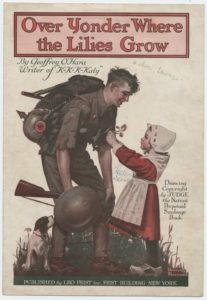

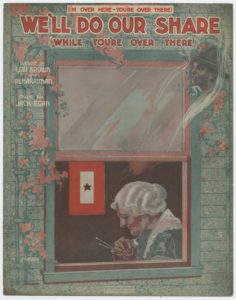

During the World War I years of 1917 to 1919, the U. S. Government requested that industries using consumable products begin to conserve these materials — including paper goods. A smaller 7” x 10” sheet music format was introduced by some publishers, shrinking the cover art and even condensing multiple pages of music. Examples from our collections of World War I songs published in this smaller format include “An Irishman Was Made To Love and Fight” and “K-K-K-Katy.”

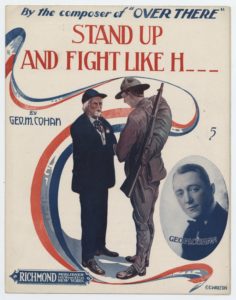

George M. Cohan and “Over There”

In 1917, Irish American George M. Cohan wrote the song that would make him an international name. “Over There” was written while Cohan was riding on a train to New York after hearing the news that America had entered the Great War. The song became a smash hit and quickly sold over a million copies. It became the rallying song for American troops and to this day is the one song most Americans associate with World War I. Twenty-five years later President Franklin D. Roosevelt would present to Cohan the Congressional Medal of Honor for the uplifting spirit it brought to American troops.

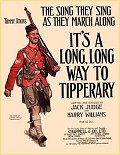

“It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary”

“It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary” (also known as “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary”) actually predates World War I, although it became popular and associated with the war. Originally a British music hall song written by Jack Judge and co-credited to Harry Williams, journalist George Curnock reported that the Irish regiment of the Connaught Rangers sang the song as they marched through Boulogne on August 13, 1914. Other British army units picked up the song quickly thereafter. John McCormack, the famous tenor, recorded “It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary” in November 1914 which helped increase its popularity.

Other composers cashed in on this popularity by writing other “Tipperary” themed World War I songs: “I’m a Long Way From Tipperary,” “I’m Going Back to Tipperary,” and “It May Be Far To Tipperary It’s a Longer Way To Tennessee” are a few examples.

Ireland, Home Rule, and the Great War

A major political crisis over Home Rule or Irish self-government occurred before the outbreak of the First World War. The Third Home Rule Act was signed into law in September of 1914, although operation of the Bill was suspended during the war. The start of the war in 1914 temporarily defused armed tensions between Unionists and Nationalists. A total of 206,000 Irish served in the British forces during the war.

The participants of the 1916 Easter Rising sought and received aid from Germany during the war. However, the shipment of arms was intercepted and destroyed off the coast of County Kerry by British forces before the uprising began.

This all led to the creation of songs such as “Volunteer March – Song” and “When Germany Licks England Old Ireland Will Be Free” by Charles A. Meyers in 1915, which was published in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Interestingly enough, Meyers also wrote “We’re Going to Show the Kaiser the Way to Cut Up Sauerkraut” later in 1918.

La Grande Guerra servi’ indubbiamente anche da catalizzatore per produrre una generosa quantita’ di scrittori, diaristi, poeti e musicisti in tutta Europa e persino oltreoceano. Un avvenimento come la guerra globale di un secolo fa, tanto spaventosa e sanguinosa da essere reputata “il conflitto che avrebbe messo fine a tutti i conflitti” non poteva essere di certo ignorata da tutti uomini di penna che l’hanno vissuto direttamente o indirettamente: perciò molti sono quelli che hanno scritto in materia cogliendone i vari aspetti secondo il proprio modo di sentire e la propria indole. Mentre le nostre antologie scolastiche spesso si limitano a proporre i lavori lirici o la tipica prosa di quel periodo (vedi gli Ungaretti, i d’Annunzio, i  Monelli, gli Jahier, ecc.), non bisogna assolutamente dimenticare le testimonianze piu’ umili, ma per questo indubbiamente piu’ spontanee e dirette, di tutti i “cantori” della Prima Guerra Mondiale, di tutti quei bardi del “blues delle trincee”.

Monelli, gli Jahier, ecc.), non bisogna assolutamente dimenticare le testimonianze piu’ umili, ma per questo indubbiamente piu’ spontanee e dirette, di tutti i “cantori” della Prima Guerra Mondiale, di tutti quei bardi del “blues delle trincee”.

Certamente le canzoni di guerra sono uno degli elementi fondamentali per la cristallizzazione della memoria della Grande Guerra. Sono al centro di una specie di reversibilità di qualità civili e militari che, durante il conflitto, vengono richiamate a guisa di anatema e ragione ultima per la quale si soffre, si combatte e si sogna un rientro nella società civile della pace. L’ideale di quest’ultima aiuta il combattente a sopportare fatiche, privazioni e dolori, mentre le virtù e le doti militari, legate al senso del dovere, coadiuvano analogamente gli sforzi per l’agognata pace.

La musica, semplice ma diretta al cuore, unita a parole profonde e solo apparentemente “facili” da rimare in poche strofe, si offrono come un vero e proprio arsenale identitario due importanti miti della Grande Guerra: quello degli Alpini in Italia (particolarmente prolifici nel “musicare” le loro leggendarie gesta) e quello dei “Tommies”, i soldati inglesi, che ci hanno lasciato come testamento anche poche, semplici e spesso scanzonate melodie. Le canzoni di guerra britanniche hanno avuto una genesi di tipo piu’ tradizionale di quelle nate direttamente durante il conflitto, come quelle ad esempio del Corpo degli Alpini italiano. Mentre queste ultime furono perlopiu’ intonazioni spontanee della sofferenza e del dolore provato in guerra (un po’ come avvenne nella musica blues e spiritual delle popolazioni di colore americane), fu la propaganda a scrivere e musicare un genere musicale idealmente destinato a sollevare lo spirito e rinfrancare i “Tommies” costretti nel fango delle trincee.

Canzoni come “Pack up your troubles”, “Take me back to dear old Blighty” e “It’s a long way to tipperary” si imposero, gia’ all’inizio del conflitto, come inni di propaganda , tanto per i soldati in partenza per il fronte, che per la popolazione rimasta a casa – un po’ come “La leggenda del Piave”, in questo genere musicale si poteva ritrovare e promuovere subito l’unita’ sociale di patria, sposando per l’immaginario collettivo i sacrifici degli eroi al fronte, con gli ideali di pace, vittoria e sbarazzina supremazia con cui si doveva anestetizzare la popolazione intera.

E’ bene ricordare che all’inizio del secolo scorso, la propaganda militare e politica era forse l’unico strumento di comunicazione che, per quanto altamente viziato e parziale, poteva raggiungere le masse, altrimenti totalmente ignare di cio’ che accadeva al fronte. Dopo il 1915 tuttavia, il terrificante numero di caduti, la perdita pressoche’ totale di tutto l’esercito professionale del secolo precedente, e la quantita’ di lutti che colpi’ anche ciascun piccolo paese in Inghilterra, costrinse autori e compositori ad interpretare in qualche modo anche questa “perdita dell’innocenza” ed il pensiero comune che la guerra non sarebbe poi finita’ cosi’ presto come si credeva.

1915 tuttavia, il terrificante numero di caduti, la perdita pressoche’ totale di tutto l’esercito professionale del secolo precedente, e la quantita’ di lutti che colpi’ anche ciascun piccolo paese in Inghilterra, costrinse autori e compositori ad interpretare in qualche modo anche questa “perdita dell’innocenza” ed il pensiero comune che la guerra non sarebbe poi finita’ cosi’ presto come si credeva.

Nascono percio’ inni alla Patria e alla famiglia lontana, che forse i piu’ fortunati riusciranno a rivedere, come “There’s a long long trail” e “Keep your home fires burning”. Non a caso, i soldati che marciano verso il fronte intonano solo questi ultimi “esorcismi musicali” contro la morte certa che li attende, dimentichi di ogni falsa promessa trasmessa all’inizio della guerra e scanzonatamente intonata a bordo di una tradotta. E’ da notare comunque, che il tema della morte, della perdita e del sacrificio non appare quasi mai fino alla fine della guerra – gli inglesi, da sempre ostinatamente conservatori ed orgogliosi della loro privacy, preferiscono fino all’ultimo credere ad una risoluzione positiva di quattro anni di dolore e sacrificio, piuttosto che soccombere di fronte agli eventi e concedersi pubblicamente anche un solo grido di scoramento o disperazione.

“Dictionary of Tommie’s Songs and Slang, 1914-1918” e’ un capolavoro di ricerca e testimonianza, pubblicato nella sua prima edizione negli anni ’30, e oggi riproposto dal Daily Telegraph con una preziosa introduzione di Malcom Brown. Il volume raccoglie praticamente tutti gli inni e le canzoni dei soldati britannici, appartenenti alla British Expeditionary Force, al corpo degli ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) e a tutti i vari contigenti coloniali. Gli autori, veterani della Grande Guerra, compilarono infatti un’approfondita ricerca di testi, melodie e persino espressioni caratteristiche dello “slang” anglosassone della Prima Guerra Mondiale.

Pare addirittura che alla stesura definitiva del loro manoscritto abbia partecipato attivamente anche il colonnello T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence d’Arabia), apportando modifiche e commenti in base alla sue esperienza di guerra mediorientale.

Alongside the national anthems of the allied powers, and the traditional “travelling songs”, very many “patriotic songs” which were aimed at uniting the Nation in a tremendous surge of republicanism, bore witness to the principal military movements, in Belgium then in France; the fall of the bastions of Liège and Namur, the siege of Paris and the requisitioning of the taxis for the Marne were recounted with bellicose and vengeful enthusiasm which portrayed the enemy as something to be demonized and ridiculed. For indeed the “krauts” were accused of being responsible for the worst atrocities throughout the war, such as raping French women and killing children: L’enfant au p’tit fusil de bois, Il est foutu Guillaume!, Gavroche dans la tranchée, Ballade impériale and L’enfant au p’tit fusil de bois

With the war entering a stalemate from the autumn of 1914, the determination and hope for a quick end to the conflict progressively gave way to the harsh reality of the battlefields. References to the dead and wounded would start to appear in the lyrics and on the illustrated covers of the songs which immortalised their contribution to the war.

Whilst at the same time, at the Panthéon the talk was of the heroes of Valmy and the Great Army, and even Jeanne d’Arc, to fill the conscripts with the stomach for battle and encourage the youngest to enlist. Charity work to support the wounded and their families was intensified. From November 1914, with the reopening of the theatres in the rear echelons and the establishment of the army theatres, songs for entertaining started to appear, often full of propaganda or happy sentiments, as an antidote to the boredom experience by the soldiers stuck in their trenches, and as a way of providing them with a form of contact with the rear echelons. The musicians who were called up or posted to the front such as the songwriter Théodore Botrel or the composer André Caplet, author of the famous Marche de Douaumont (March of Douaumont) would use their talent to help out the Army. The rear echelons were treated to performances of “real-life songs” which played up sentimental or comical emotions, in a popular language which was often rich in colour to the point of containing slang taken from working songs. The musical scores which were more often than not written or composed by amateur authors (60% of them would remain anonymous), would be restricted to a melody without any accompaniment, using known lyrics and tunes. In the form of choruses and couplets based on polka or marching rhythms, they would be all about the daily life in the trenches, honouring in turn the different arms and jobs from the “poilu” (infantryman) or the “bleuet” (blue uniformed infantrymen of 1915), to the airmen, not forgetting the “chauffards” drivers, the stretcher bearers, the nurses and the health services. The rear echelons were not to be outdone with their long list of stereotypes: French women reduced once more to their traditional role of devoted mothers, sisters and wives, specialist workers called up to the rear echelons to contribute to the war effort in the “cannon and ammunitions” factories. The bayonet, the machine gun as well as the famous 75mm field gun, which were the soldiers’ faithful companions and the pride of the French army at the start of the war, provided the rhythm to the songs with their noise whereas the love stories and other “three penny romances”, were intended to take the soldiers’ and people’s minds off the horrors of war. The illustrated covers, which were very rarely signed, sometimes set to colour (in the colours of the French flag which was itself very much in evidence) despite these difficult years, were in tune with the language used: the aesthetics just like the melody, which could be serious or for dancing, scholarly or simplistic, rousing or poignant, would fit in with the type of language in the song.

Alongside what was an “easy” repertoire, there were also lyrics with a high literary and musical content, coming from established authors, from often conservative backgrounds (Charles Péguy, for example), and from professional musicians (Claude Debussy) many of whom performed at concerts on the front line. As varied as they were, these edited songs were none the less the tools of the propaganda machine and were subject to rigorous censorship. This was how the song Les héros de Craonne, (The heroes of Craonne) which was written in 1918 as a tribute to the Paquette division which sacrificed itself on 5 May 1917, was claimed to be the reply to the famous Chanson de Craonne. Song of Craonne itself was censured because of its subversive nature with regard to the Nation and whose anonymous author was never unmasked despite the rewards which were promised… Although peace was sometimes mentioned, it was because it was to be fought for in a just war “for freedom and the defence of humanity” in 1914, but the peace which was to be earned through a vast Fraternity movement, which implied the refusal to fight, emerged at the end of 1916:

“After so much pain, the hatred

Will finally give way to Fraternity!

No more bloody fighting, no more pointless slaughter,

So let mankind live in peace from now on!

Chorus

…

Let the World

Fight together as one

So that Peace will triumph!”

Find the full French song here.

The Importance of Songs During the War

Whether they had a message or were a simple form of entertainment, songs were a key part of life in society at this the beginning of the 20th century. The songs which would be churned out for popular consumption hailed from a long tradition, stretching back to the Revolution, taking in songwriters such as Béranger and Jean-Baptiste Clément, and they came in all sorts of forms for all sorts of audiences and causes. Very different in their themes from the traditional religious and children’s songs, the happily-ending romances were the most common on the cabaret stage. Because they were oral by nature, these popular songs were produced and widely heard in the form of very cheap small versions, of which a number took on a new stature from the end of the century by means of illustrations which sometimes bore the signature of great names and which were sold in the street or as a supplement to magazines and daily newspapers. Songs with a social or political message, also lived on, carried by the voices of singer songwriters and contained numerous examples of anticlerical, anarchist and antimilitarist feeling which ran through pre-1914 society.

One may have thought that the First World War, with all its barbarity, might have silenced the songwriters and starved the people of their “thirst for songs”. Not at all. Folks would sing on their way to the front, they would sing in the rear echelons, to stoke up their courage, and despite everything else to entertain themselves. Nevertheless there was a hint, through the new and revisited themes, of the hardship that everyone was experiencing. Out of more than 300 small versions of the songs from the Great War kept at the department of Music of the BnF (French National Library), around 70% (215) came out during 1915 alone, compared to 45 in 1914 and 37 between 1916 and 1918 .

During the two first years of the First World War, patriotic songs enjoyed a major resurgence, similar to that seen after the defeat of 1871. Very popular tunes or lyrics such as the Marseillaise or the revolutionary song, the Carmagnole, were often covered. (La Carmagnole du Kaiser, The Carmagnole of the Kaiser) (La française, sur air de la marseillaise, The Frenchwoman to the tune of the Marseillaise) on the label.

TESTI

My Dear H.J.,

You have often asked me what are the favourite songs of the soldier on Active Service, the rhymed lines which give expression to his soul. It is difficult to give an answer, the mere words are “dud”shells, which drop harmlessly to earth close to their objective. The soldier and his song cannot be separated from their surroundings.

Let me explain and quote in illustration an incident which occurred a few weeks ago.

A certain regiment, which glories in the name of the “Old Diehards,”sent a draft to the “London Irish,”and the new-comers attached to our battalion became part of the units’ fighting strength. Sixty per cent of the draft were “old sweats,”men who had fought well on many a bloody field, and added by prowess of arms numerous honours to their own beloved regiment. They had shared their last crust with hearty comrades in the retreat from Mons, they battled side by side with these comrades on the Marne, and wept over their graves by the Aisne.

The circumstances of war strengthen the esprit-de-corps of a soldier, and I am not far wrong in stating that pride of regiment in an “old sweat”is much stronger than love of country. On the evening of their arrival these veterans sat in their huts and sang the song the “Old Diehards.”Mere doggerel the verse, the words fatuous, and the singing not above reproach. But the song touched the hearts of the audience; the listeners were “old sweats”who had songs of their own.

As I listened I thought of the children of Israel, who hung their harps on the willows and mourned for Babylon. The feeling engendered in a man when a futile shell drops close to him and fails to explode is difficult to make manifest in cold words; but it is even more difficult to give an adequate idea of the impression created in the hearts of those who listened to the song of the “Old Diehards.”The soldiers have songs of their own, songs of the march, the trench, the billet and battle. Their origin is lost; the songs have arisen like old folk tales, spontaneous choruses that voice the moods of a moment and of many moments which are monotonously alike. Most of the verse is of no import; the crowd has no sense of poetic values; it is the singing alone which gives expres sion to the soldier’s soul. “Tipperary “means home when it is sung in a shell shattered billet, on the long march “Tipperary”is Berlin, the goal of high emprise and great adventures.

Let me speak of a few songs which we sing. This is our idea of the peace which may follow our years of war.

When the war is over

We’re going to live in Dover,

When the war is over we’re going to have a spree,

We’re going to have a fight

In the middle of the night

With the whizz-bangs a-flying in the air.

Though we cannot picture a peace which will be in no way associated with high explosives, we can dream in the midst of the conflict of the desirable things that civil life would bring us.

What time we waited for Kitchener’s Army in Flanders and lost all hope of ever seeing it, this song was sung up and down the trenches by the Territorials and Regulars.

Who are the boys that fighting’s for,

Who are the lads to win the war,

It’s good old Kitchener’s Army.

And every man of them’s très bon,

They never lost a trench since Mons,

Because they never saw one.”

Here are a few others which have echoed in billets and dug-outs from Le Harve to the Somme, and which have accompanied the wild abandon of drinking nights in Poperinghe and Bethune.

THE SOLDIER’S LETTER

I’ve lost my rifle and bayonet,

I’ve lost my pull-through too,

I’ve lost the socks that you sent me

That lasted the whole winter through,

I’ve lost the razor that shaved me,

I’ve lost my four-by-two,

I’ve lost my hold-all and now I’ve got damn all

Since I’ve lost you.”

SING ME TO SLEEP

Sing me to sleep where bullets fall,

Let me forget the war and all;

Damp is my dug-out, cold my feet,

Nothing but bully and biscuits to eat.

Over the sandbags helmets you’ll find

Corpses in front and corpses behind.

Chorus.

Far, far from Ypres I long to be,

Where German snipers can’t get at me,

Think of me crouching where the worms creep,

Waiting for the sergeant to sing me to sleep.

Sing me to sleep in some old shed,

The rats all running around my head,

Stretched out upon my waterproof,

Dodging the raindrops through the roof,

Dreaming of home and nights in the West,

Somebody’s overseas boots on my chest.

The Tommy is a singing soldier; he sings to the village patronne even when ordering food, and his song is in French.

Voulez vous donnez moi Si’l vous pläit

Pain et beurre

Et café au lait.”

He serenades the maiden at the village pomp.

Après la guerre fini

Soldat Anglais partée,

M’selle Frongsay boko pleury,

Après la guerre fini.

The soldier has in reality very few songs; he has many choruses which get worth from the mood that inspires them and the emotions which they evoke. None will outlast the turmoil in which they originated; having weathered the leaden storms of war, their vibrant strains will be choked and smothered in atmospheres of Peace. “These ‘ere songs are no good in England,”my friend Rifleman Bill Teake remarks. “They ‘ave too much guts in them.”

When I said I wanted to dedicate “Soldier Songs”to you I did not then anticipate inflicting upon you so lengthy a dedicatory letter; but when writing of the men of the British armies, old and new, I find it difficult to be concise.

Yours,

Patrick MacGill

Lammas Day, 1916

AFTER LOOS

(Cafe Pierre le Blanc, Nouex les Mines, Michaelmas Eve, 1915) <P.

WAS it only yesterday

Lusty comrades marched away ?

Now they’re covered up with clay.

Seven glasses used to be

Called for six good mates and me —

Now we only call for three.

Little crosses neat and white,

Looking lonely every night,

Tell of comrades killed in fight.

Hearty fellows they have been,

And no more will they be seen

Drinking wine in Nouex les Mines.

Lithe and supple lads were they,

Marching merrily away —

Was it only yesterday?

THE OLE SWEATS

(1st Birmingham War Hospital, Ruberry, Birmingham.)

WE’RE goin’ easy now a bit, all dressed in blighty blue.*

We’ve ‘eld the trenches eighteen months and

copped some packets too,

We’ve met the Boches on the Marne and fought

them on the Aisne,

We broke ‘em up at New Chapelle and ‘ere we

are again.

The ole sweats —

All that is left of the ole sweats.

More went away than are with us to-day.

Gawd I but we miss ‘em, the ole sweats.

And now that we’ve a blighty one** we don’t

know what to do! —

Just swing the lead; the Darby boys will see

the bisness through,

They’ll ‘ave a bit o’ carry on, o’ fightin’ and o’ fun,

They’ll ‘ave the ribbons when they end the

work that we begun.

The ole sweats —

Devils for fun were the ole sweats,

In love or a scrap sure they always went nap,

They ‘adn’t ‘arf guts had the ole sweats.

But the old sweats they never die, they only

fade away And others come to take their place, ‘ot on

the doin’s they;

They’re drillin’ up from day to day, at it at

dusk and dawn,

But they’ll need it all to fill the shoes of blokes

that now are gone;

The ole sweats,

The ole daisy-shovers,*** the ole sweats.

The new ‘uns it’s said they are smart on

parade,

But, Gawd, there is none like the ole sweats.

We’re out ‘t for duration now and do not care

a cuss,

There’s beer to spare at dinner time and afters+

now for us,

But if our butty’s still were out in Flanders

raisin’ Cain,

We’d weather through with those we knew on

bully beef again.

The ole sweats —

The grub it was skimp with the ole sweats.

But if rashuns was small ‘twas the same for

us all,

Same for the ‘ole of the ole sweats.

Well, if you want a sooveneer, a bit of blighty

blue,

There’s empty tunic sleeves to spare, a trousers

leg or two,

And some day when you see us stand on

Charing Cross parade,

Present a boot before us just to ‘elp us at our

trade.

The ole sweats —

Tuppence a shine with the ole sweats.

So you’ll give us a show when you see us, we

know,

Us that is left of the ole sweats.

- Hospital uniform

- A blighty one. A wound which brings a soldier back to England.

- Daisy-shovers. The dead; “the men who lie under the ground, shoving the daisies up with their toes.”

- A blighty one. A wound which brings a soldier back to England.

+ Afters = confiture.

LA BASSEE ROAD

(Cuinchy, 1915.)

YOU’LL see from the La Bassée Road, on any

summer’s day,

The children herding nanny-goats, the women

making hay.

You’ll see the soldiers, khaki clad, in column

and platoon,

Come swinging up La Bassée Road from billets

in Bethune.

There’s hay to save and corn to cut, but harder

work by far

Awaits the soldier boys who reap the harvest

fields of war.

You’ll see them swinging up the road where

women work at hay,

The straight long road, — La Bassée Road, — on

any summer day.

The night-breeze sweeps La Bassée Road, the

night-dews wet the hay,

The boys are coming back again, a straggling

crowd are they.

The column’s lines are broken, there are gaps

in the platoon,

They’ll not need many billets, now, for soldiers

in Bethune,

For many boys, good lusty boys, who marched

away so fine,

Have now got little homes of clay beside the

firing line.

Good luck to them, God speed to them, the

boys who march away,

A-singing up La Bassée road each sunny é summer day. é

A LAMENT

(The Ritz-Loos Saient.)

I WISH the sea were not so wide

That parts me from my love;

I wish the things men do below

Were known to God above.

I wish that I were back again

In the glens of Donegal,

They’ll call me coward if I return,

But a hero if I fall.

“Is it better to be a living coward,

Or thrice a hero dead?”

“It’s better to go to sleep, my lad,”

The Colour Sergeant said.

THE GUNS

(Shivery-shake Dug-out, Marne.)

THERE’S a battery snug in the spinney,

A French seventy-five in the mine,

A big nine-point-two in the village

Three miles to the rear of the line.

The gunners will clean them at dawning

And slumber beside them all day,

But the guns chant a chorus at sunset,

And then you should hear what they say.

Chorus.

Whizz bang! pip squeak! ss-ss-st!

Big guns, little guns waken up to it.

We’re in for heaps of trouble, dug-outs at

the double,

And stretcher-bearers ready to tend the

boys who’re hit.

And then there’s the little machine-gun, —

A beggar for blood going large.

Go, fill up his belly with iron,

And he’ll spit in the face of a charge.

The foe fixed his ladders at daybreak,

He’s over the top with the sun;

He’s waiting; for ever he’s waiting,

The pert little vigilant gun.

Chorus

Its tit-tit! tit-tit! tit! tit! tit!

Hark the little terror bristling up to it!

See his victims lying, wounded sore and

dying —

Red the field and volume on which his name

is writ.

The howitzer lurks in an alley,

(The howitzer isn’t a fool,)

With a bearing of snub-nosed detachment

He squats like a toad on a stool.

He’s a close-lipped and masterly beggar,

A fellow with little to say,

But the little he says he can say in

A most irrepressible way.

Chorus

OO — plonk! OO-plonk! plonk! plonk!

plonk!

The bomb that bears the message riots

through the air.

The dug-outs topple over on the foemen

under cover,

They’ll slumber through revelly who get

the message there!

The battery barks in the spinney,

The howitzer plonks like the deuce,

The big nine point two speaks like thunder

And shatters the houses in Loos,

Sharp chatters the little machine-gun,

Oh! when will its chattering stop ? —

At dawn, when we swarm up the ladders;

At dawn we go over the top!

Chorus

Whizz bang! pipsqueak! OO-plonk! sst!

Up the ladders! Over! And carry on

with it

The guns all chant their chorus, the shells

go whizzing o’er us: —

Forward, hearties! Forward to do our

little bit!

THE NIGHT BEFORE AND THE NIGHT

AFTER THE CHARGE

ON sword and gun the shadows reel and riot,

A lone breeze whispers at the dug-out door,

The trench is silent and the night is quiet,

And boys in khaki slumber on the floor.

A sentinel on guard, my watch I keep

And guard the dug-out where my

comrades sleep.

The moon looks down upon a ghost-like figure,

Delving a furrow in the cold, damp sod.

The grave is ready and the lonely digger

Leaves the departed to their rest and God.

I shape a little cross and plant it deep

To mark the dug-out where my comrades sleep.

IT’S A FAR, FAR CRY

My heart is sick of the level lands,

Where the wingless windmills be,

Where the long-nosed guns from dusk to dawn

Are speaking angrily;

But the little home by Glenties Hill,

Ah! that’s the place for me.

A candle stuck on the muddy floor

Lights up the dug-out wall,

And I see in its flame the prancing sea

And the mountains straight and tall;

For my heart is more than often back

By the hills of Donegal.

OFF DUTY

THE night is full of magic, and the moonlit

dewdrops glisten

Where the blossoms close in slumber and the

questing bullets pass —

Where the bullets hit the level I can hear them

as I listen,

Like a little cricket concert, chirping chorus in

the grass.

In the dug-out by the traverse there’s a candle-

flame a-winking

And the fireflies on the sandbags have their

torches all aflame.

As I watch them in the moonlight, sure, I

cannot keep from thinking,

That the world I knew and this one carry on

the very same.

I OFT GO OUT AT NIGHT-TIME

I OFT go out at night-time

When all the sky’s a-flare

And little lights of battle

Are dancing in the air.

I use my pick and shovel

To dig a little hole,

And there I sit till morning —

A listening-patrol.

A silly little sickle

Of moon is hung above;

Within a pond beside me

The frogs are making love:

I see the German sap-head;

A cow is lying there,

Its belly like a barrel,

Its legs are in the air.

The big guns rip like thunder,

The bullets whizz o’erhead,

But o’er the sea in England

Good people lie abed.

And over there in England

May every honest soul

Sleep sound while we sit watching

On listening patrol.

THE CROSS

(On the grave of an unknown British soldier, Givenchy, 1915 )

THE cross is twined with gossamer, —

The cross some hand has shaped with care,

And by his grave the grasses stir

But he is silent sleeping there.

The guns speak loud: he hears them not;

The night goes by: he does not know;

A lone white cross stands on the spot,

And tells of one who sleeps below.

The brooding night is hushed and still,

The crooning breeze draws quiet breath,

A star-shell flares upon the hill

And lights the lowly house of death.

Unknown, a soldier slumbers there,

While mournful mists come dropping low,

But oh! a weary maiden’s prayer,

And oh! a mother’s tears of woe.

THE TOMMY’S LAMENT

(The Ritz-Loos Salient.)

I FANCY it’s not ‘arf my chance

To go on plodding ‘neath my pack,

Parading like a snail through France,

My house upon my bloomin’ back.

My wants are few, but what I need

Ain’t not so much of bully stew,

Nor biscuits, that’s a mongrel’s feed,

But, matey, just ‘twixt me and you —

When winks the early evening star,

And shadows o’er the trenches come —

I wish the sergeants brought a jar,

And issued double tots of rum.

MARCHING

(La Bassée Road, June, 1915.)

FOUR by four, in column of route,

By roads that the poplars sentinel,

Clank of rifle and crunch of boot —

All are marching and all is well.

White, so white is the distant moon,

Salmon-pink is the furnace glare

And we hum, as we march, a ragtime tune,

Khaki boys in the long platoon,

Ready for anything — anywhere.

Lonely and still the village lies,

The houses sleep and the blinds are drawn,

The road is straight as the bullet flies,

And we go marching into the dawn;

Salmon-pink is the furnace sheen.

Where the coal stacks bulk in the ghostly air

The long platoons on the move are seen,

Little connecting files between,

Moving and moving, anywhere.

IN FAIRYLAND

THE field is red with poppy flowers,

Where mushroom meadows stand;

It’s only seven fairy hours

From there to Fairyland.

Now when the star-shells riot up

In flares of red and green,

Each fairy leaves her buttercup

And goes to see her queen.

Where little, ghostly moonbeams stray

Through mushroom alleys white,

The fairies carry on their way

A glow-worm lamp for light.

For them the journey’s always short;

They’re happy as you please,

A-riding to the Fairy Court

On backs of bumble-bees.

The cricket and the grasshopper

Are thridding in the grass,

And making paths of gossamer

For fairy feet to pass.

Whene’er I see a glow-worm light

In Boyau seventeen,

I know the fairies go that night

To see the Fairy Queen.

SPOILS OF WAR

I HAVE a big French rifie, its stock is riddled

clean,

And shrapnel-smashed its barrel, likewise its

magazine.

I’ve lugged it from Bethune to Loos and back

from Loos again,

I’ve found it on the battlefield amidst the

soldiers slain.

A little battle souvenir for one across the foam

That’s if the French authorities will let me

take it home.

I’ve got a long, long sabre as sharp as any

lance,

‘Twas carried by a shepherd boy from some-

where South in France

Where grasses wave and poppy-flowers are red

as blood is red,

I took the shepherd’s sabre for the shepherd

boy lay dead.

I’ll take it back a souvenir to one across the

foam.

That’s if the French authorities will let me

take it home,

That’s if our own authorities will give me leave

for home!!!

BEFORE THE CHARGE

(Loos, 1915.)

THE night is still and the air is keen,

Tense with menace the time crawls by,

In front is the town and its homes are seen,

Blurred in outline against the sky.

The dead leaves float in the sighing air,

The darkness moves like a curtain drawn,

A veil which the morning sun will tear

From the face of death. — We charge at dawn.

LETTERS

( Vermelles, August, 1915.)

WHEN stand-to hour is over we leave the

parapet,

And scamper to our dug-out to smoke a

cigarette;

The post has brought in parcels and letters for

us all,

And now we’ll light a candle, a little penny

candle,

A tiny tallow candle, and stick it to the wall.

Dark shadows cringe and cower on roof and

wall and floor,

And little roving breezes come rustling through

the door;

We open up the letters of friends across the

foam,

And thoughts go back to London, again we

dream of London —

We see the lights of London, of London and of

home.

We’ve parcels small and parcels of a quite

gigantic size,

We’ve Devon cream and butter and apples

baked in pies,

We’ll make a night of feasting and all will have

their fill —

See, cot-mate Bill has dainties, such dandy,

dinky dainties,

She’s one to choose the dainties, the maid

that’s gone on Bill.

Oh: Kensington for neatness; it packs its

parcels well,

Though Bow is always bulky it isn’t quite as

swell,

But here there’s no distinction ‘twixt Kensing-

ton and Bow,

We’re comrades in the dug-out, all equals in

the dug-out,

We’re comrades in the dug-out and fight a

common foe.

Here comes the ration party with tins of bully

stew —

“Clear off your ration party, we have no need

of you;

“Maconachie for breakfast ? It ain’t no

bloomin’ use,

We’re faring far, far better, our gifts from

home are better,

Look here, we’ve something better than bully

after Loos.”

The post comes trenchward nightly; we hail

the post with glee,

Though now we’re not as many as once we

used to be,

For some have done their fighting, packed up

and gone away,

And many boys are sleeping, no sound will

break their sleeping,

Brave lusty comrades sleeping in little homes

of clay.

We all have read our letters, but one’s un-

touched so far,

An English maiden’s letter to her sweetheart

at the War,

And when we write in answer to tell her how

he fell,

What can we say to cheer her ? Oh, what is

now to cheer her ?

There’s nothing left to cheer her except the

news to tell.

We’ll write to her to-morrow and this is what

we’ll say,

He breathed her name in dying; in peace he

passed away —

No words about his moaning, his anguish and

his pain,

When slowly, slowly dying. God! Fifteen

hours in dying

He lay a maimed thing dying, alone upon the

plain.

We often write to mothers, to sweethearts and

to wives,

And tell how those who loved them have given

up their lives;

If we’re not always truthful, our lies are always

kind,

Our letters lie to cheer them, to solace and to

cheer them,

Oh: anything to cheer them, — the women left

behind.

THE EVERYDAY OF WAR

(Hospital, Versailles, November, 1915.)

A HAND is crippled, a leg is gone,

And fighting’s past for me,

The empty hours crawl slowly on;

How they flew where I used to be!

Empty hours in the empty days,

And empty months crawl by,

The brown battalions go their way,

And here at the Base I lie!

I dream of the grasses the dew-drops drench,

And the earth with the soft rain wet,

I dream of the curve of a winding trench,

And a loop-holed parapet;

The sister wraps my bandage again,

Oh, gentle the sister’s hand,

But the smart of a restless longing, vain,

She cannot understand.

At night I can see the trench once more,

And the dug-out candle lit,

The shadows it throws on wall and floor

Form and flutter and flit.

Over the trenches the night-shades fall

And the questing bullet pings,

And a brazier glows by the dug-out wall,

Where the bubbling mess-tin sings.

I dream of the long, white, sleepy night

Where the fir-lined roadway runs

Up to the shell-scarred fields of fight

And the loud-voiced earnest guns;

The rolling limber and jolting cart

The khaki-clad platoon,

The eager eye and the stout young heart,

And the silver-sandalled moon.

But here I’m kept to the narrow bed,

A maimed and broken thing —

Never a long day’s march ahead

Where brown battalions swing.

But though time drags bylike a wounded snake

Where the young life’s lure’s denied,

A good stiff lip for the old pal’s sake,

And the old battalion’s pride!

The ward-fire burns in a cheery way,

A vision in every flame,

There are books to read and games to play

But oh! for an old, old game,

With glancing bay-net and trusty gun

And wild blood, bursting free! —

But an arm is crippled, a leg is gone,

And the game’s no more for me.

THE LONDON LADS

(While standing to arms in billets, La Beuvrire, July, 1915.)

ALONG the road in the evening the brown

battalions wind,

With the trenches’ threat of death before, the

peaceful homes behind;

And luck is with you or luck is not as the ticket

of fate is drawn,

The boys go up to the trench at dusk, but who

will come back at dawn?

The winds come soft of an evening o’er the

fields of golden grain,

The good sharp scythes will cut the corn ere we

come back again;

The village girls will tend the grain and mill the

Autumn yield

While we go forth to other work upon another

field.

They’ll cook the big brown Flemish loaves and

tend the oven fire,

And while they do the daily toil of barn and

bench and byre

They’ll think of hearty fellows gone and sigh

for them in vain —

The billet boys, the London lads who won’t

THE LITTLE BROWN BIRD

THERE’S a little brown bird in the

spinney,

With a little gold cap on its head,

Gold as the gold of a guinea,

And its legs they are wobbly and

red.

MYSELF. “Little brown bird, is your singing

Over and finished and done?”

BIRD. “I wait for the fairy who’s bringing

Spring and its showers and its sun.”

MYSELF. “What will you do in December?”

BIRD. “Do? What I’m doing just now:

Here on the first of November,

Shivering mute on a bough.”

MYSELF. “But April will find you quite

cheery! “

I said with a pang in my breast.

BIRD. “In April I’ll get me a dearie

And help her to fashion a nest “

THE LISTENING-PATROL

WITH my bosom friend, Bill, armed ready to

kill,

I go over the top as a listening-patrol.

Good watch we will keep if we don’t fall asleep,

As we huddle for warmth in a shell-shovelled

hole.

In the battle-lit night all the plain is alight,

Where the grasshoppers chirp to the frogs

in the pond,

And the star-shells are seen bursting red, blue,

and green,

O’er the enemy’s trench just a stone’s-throw

beyond.

The grasses hang damp o’er each wee glow-

worm lamp

That is placed on the ground for a fairy

camp-fire,

And the night-breezes wheel where the mice

squeak and squeal,

Making sounds like the enemy cutting our

wire.

Here are thousands of toads in their ancient

abodes,

Each toad on its stool and each stool in its

place,

And a robin sits by with a vigilant eye

On a grim garden-spider’s wife washing her

face.

Now Bill never sees any marvels like these,

When I speak of the sights he looks up with

amaze,

And he smothers a yawn, saying, “Wake me at

dawn,”

While the Dustman from Nod sprinkles dust

in his eyes.

But these things you’ll see if you come out

with me,

And sit by my side in a shell-shovelled hole,

Where the fairy-bells croon to the ivory moon

When the soldier is out on a listening-patrol.

A VISION

THIS is a tale of the trenches

Told when the shadows creep

Over the bay and traverse

And poppies fall asleep.

When the men stand still to their rifles,

And the star-shells riot and flare,

Flung from the sandbag alleys,

Into the ghostly air.

They see in the growing grasses

That rise from the beaten zone

Their poor unforgotten comrades

Wasting in skin and bone,

And the grass creeps silently o’er them

Where comrade and foe are blent

In God’s own peaceful churchyard

When the fire of their might is spent.

But the men who stand to their rifles

See all the dead on the plain

Rise at the hour of midnight

To fight their battles again.

Each to his place in the combat,

All to the parts they played

With bayonet, brisk to its purpose,

Rifle and hand grenade.

Shadow races with shadow,

Steel comes quick on steel,

Swords that are deadly silent

And shadows that do not feel.

And shades recoil and recover

And fade away as they fall

In the space between the trenches,

And the watchers see it all.

THE HIPE

“WHAT do you do with your rifle, son ?”I

clean it every day,

and rub it with an oily rag to keep the rust

away;

I slope, present, and port the thing when

sweating on parade.

I strop my razor on the sling; the bayonet

stand is made

For me to hang my mirror on. I often use it,

too,

As handle for the dixie, sir, and lug around the

stew.

“But did you ever fire it, son?”Just once,

but never more.

I fired it at a German trench, and when my

work was o’er

The sergeant down the barrel glanced, and

then he said to me,

“Your hipe* is dirty. Penalty

is seven days’

C.B.!”

- Hipe, regimental slang for a rifle

THE TRENCH

THE long trench, twisting, turning, wanders

wayward as a rlver

Through the poppy-flowers blooming in the

grasses dewy wet,

The buttercups sit shyly and the daisies nod

and quiver,

Where the bright defiant bayonets rim the

sandbagged parapet,

In the peaceful dawn the trenches hold a

menace and a threat.

The last faint evening streamer touches heaven

with its finger,

The vast night’s starry legion sends its first

lone herald star,

Around the bay and traverse little twilight

colours linger

And incense-laden breezes come in crooning

from afar,

To where above the sandbags gleam the steely

fangs of war.

All the night the frogs go chuckle, all the day

the birds are singing

In the pond beside the meadow, by the

roadway poplar-lined,

In the field between the trenches are a million

blossoms springing

‘Twixt the grass of silver bayonets where the

lines of battle wind

Where man has manned the trenches for the

maiming of his kind.

ON ACTIVE SERVICE

FOR the bloke on Active Service, w’en ‘e goes

across the sea,

‘E’s sure to stand in terror of the things ‘e

doesn’t see,

A ‘and grenade or mortar as it leaves the other

side

You can see an’ ‘ear it comin’, so you simply

steps aside.

The aeroplane above you may go droppin’

bombs a bit,

But lyin’ in your dug-out you’re unlucky if

you’re ‘it.

V’en the breezes fills your trenches with

hasfixiatin’ gas,

You puts on your respirator an’ allows the

stuff to pass.

W’en you’re up against a feller with a bayonet

long an’ keen,

Just ‘ave purchase of your weapon an’ you’ll

drill the beggar clean.

W’en man and ‘oss is chargin’ you, upon your

knees you kneel,

An’ catch the ‘oss’s breastbone with an inch

or two of steel.

It’s sure to end its canter, an’ as the creature

stops

The rider pitches forward an’ you catch ‘im as

‘e drops.

It’s w’en ‘e sees ‘is danger, an’ ‘e knows ‘is way

about

That a bloke is damned unlucky if e’s knocked

completely out.

But out on Active Service there are dangers

everywhere,

The shrapnel shell and bullet that comes on

you unaware,

The saucy little rifle is a perky little maid,

An’ w’en you’ve got ‘er message you ‘ave done

your last parade.

The four-point-five will seek you from some

distant leafy wood,

An’ taps you on the napper an’ you’re out of

step for good.

From the gun within the spinney to the sniper

up a tree

There are terrors waitin’ Tommy in the things

‘e doesn’t see.

BILLETS

OUR old battalion billets still,

Parades as usual go on,

We buckle in with right good will

And daily our equipment don

As if we meant to fight, but no!

The guns are booming through the air,

The trenches call us on, but oh!

We don’t go there, we don’t go there!

At night the stars are shining bright

The old world voice is whispering near,

We’ve heard it when the moon was light,

And London’s streets were very dear;

But dearer now they are, sweetheart,

The buses running to the Strand, —

But we’re so far, so far apart,

Each lonely in a different land.

But, dear, with sentiment aside

(The candle dwindles to the cheese)*

I wish the sea were not so wide

When distance brings such thoughts as these.

One glance to see the foreign sky,

One look to note the stars o’erhead,

Sweet thoughts to you, sweetheart, and I

Turn in to billet barn, and bed.

- The Old Sweats fashion sconces from cheese.

IN THE MORNING

(Loos, 1915.)

THE firefly haunts were lighted yet,

As we scaled the top of the parapet;

But the East grew pale to another fire,

As our bayonets gleamed by the foeman’s

wire;

And the sky was tinged with gold and grey,

And under our feet the dead men lay,

Stiff by the loop-holed barricade;

Food of the bomb and the hand-grenade;

Still in the slushy pool and mud —

Ah I the path we came was a path of blood,

When we went to Loos in the morning.

A little grey church at the foot of a hill,

With powdered glass on the window-sill.

The shell-scarred stone and the broken tile,

Littered the chancel, nave and aisle —

Broken the altar and smashed the pyx,

And the rubble covered the crucifix;

This we saw when the charge was done,

And the gas-clouds paled in the rising

sun,

As we entered Loos in the morning.

The dead men lay on the shell-scarred plain,

Where Death and the Autumn held their

reign —

Like banded ghosts in the heavens grey

The smoke of the powder paled away;

Where riven and rent the spinney trees

Shivered and shook in the sullen breeze,

And there, where the trench through the

graveyard wound,

The dead men’s bones stuck over the ground

By the road to Loos in the morning.

The turret towers that stood in the air,

Sheltered a foeman sniper there —

They found, who fell to the sniper’s aim,

A field of death on the field of fame;

And stiff in khaki the boys were laid

To the sniper’s toll at the barricade,

But the quick went clattering through the

town,

Shot at the sniper and brought him down,

As we entered Loos in the morning.

The dead men lay on the cellar stair,

Toll of the bomb that found them there.

In the street men fell as a bullock drops,

Sniped from the fringe of Hulluch copse.

And the choking fumes of the deadly shell

Curtained the place where our comrades fell,

This we saw when the charge was done

And the East blushed red to the rising sun

In the town of Loos in the morning.

TO MARGARET

IF we forget the Fairies,

And tread upon their rings,

God will perchance forget us,

And think of other things.

When we forget you, Fairies,

Who guard our spirits’ light:

God will forget the morrow,

And Day forget the Night.

DEATH AND THE FAIRIES

BEFORE I joined the Army

I lived in Donegal,

Where every night the Fairies

Would hold their carnival.

But now I’m out in Flanders,

Where men like wheat-ears fall,

And it’s Death and not the Fairies

Who is holding carnival.

THE RETURN

THERE’S a tramp o’ feet in the mornin,’

There’s an oath from an N.C.O.,

As up the road to the trenches

The brown battalions go:

Guns and rifles and wagons,

Transports and horses and men,

Up with the flush of the dawnin’,

And back with the night again.

Back again from the battle,

From the mates we’ve left behind,

And our officers are gloomy

And the N.C.O.’s are kind;

When a Jew’s harp breaks the silence,

Purring an old refrain,

Singing the song of the soldier,

“Here we are again! “

Here we are!

Here we are!

Oh! here we are again!

Some have gone west,

Best of the best,

Lying out in the rain,

Stiff as stones in the open,

Out of the doings for good.

They’ll never come back to advance or attack;

But, God! don’t we wish that they could!

RED WINE

Now seven supple lads and clean

Sat down to drink one night,

Sat down to drink at Nouex-les-Mines

And then went off to fight;

And seven supple lads and clean

Are finished with the fight,

But only three at Nouex-les-Mines

Sit down to drink to-night.

And when we took the cobbled road

We often took before,

Our thoughts were with the hearty lads

Who trod that way no more.

Oh I lads out on the level fields,

If you could call to mind

The good red wine at Nouex-les-Mines

You would not stay behind.

And when we left the trench to-night,

Each weary with his load,

Grey, silent ghosts, as light as air,

Came with us down the road.

And now we sit us down to drink

You sit beside us, too,

And drink red wine at Nouex-les-Mines

As once you used to do.

THE DAWN

(Givenchy.)

THE dawn comes creeping o’er the plains,

The saffron clouds are streaked with red,

I hear the creaking limber chains,

I see the drivers raise the reins

And urge their weary mules ahead.

And men go up and men go down,

The marching hosts are grand to see

In shrapnel-shivered trench and town,

In spinneys where the leaves of brown

Are falling on the dewy lea.

Lonely and still the village lies,

The houses sleeping, the blinds all drawn.

The road is straight as the bullet flies,

The villagers fix their waking eyes

On the shrapnel smoke that shrouds the

dawn.

Out of the battle, out of the night,

Into the dawn and the blush of day,

The road that takes us back from the fight,

The road we love, it is straight and white,

And it runs from the battle, away, away.

THE FLY

BUZZ-FLY and gad-fly, dragon-fly and blue,

When you’re in the trenches come and visit

you,

They revel in your butter-dish and riot on your

ham,

Drill upon the army cheese and loot the

army jam.

They’re with you in the dusk and the dawning

and the noon,

They come in close formation, in column and

platoon.

There’s never zest like Tommy’s zest when

these have got to die:

For Tommy takes his puttees off and strafs the

blooming fly.

OUT YONDER

You may see his eye shine brightly, for he bears

his burden lightly,

As he makes his journey nightly up the long

road from Bethune,

With his bayonet briskly swinging, and you’ll

hear him singing, singing,

In the silence and the silver, molten silver, of

the moon.

Young and eager — bright his face is, spirit of

the shrapneled places

Where the homes are battered, broken, and the

land in ruin lies.

But the young adventure burning gives him

never time for yearning,

And the natal flame of roving gleams like

lightning in his eyes.

What awaits you, boy, out yonder, where the

great guns rip and thunder ?

There’s a menace in their message — guns that

called you from afar.

But where’er your fortunes guide you may no

woe or ill betide you —

Heaven speed you, little soldier, gaily going to

the war.

I WILL GO BACK

I’LL go back again to my father’s house and live

on my father’s land —

For my father’s house is by Rosses’ shore that

slopes to Dooran strand,

And the wild mountains of Donegal rise up on

either hand.

I have been gone from Donegal for seven years

and a day,

And true enough it’s a long, long while for a

wanderer to stay —

But the hills of home are aye in my heart and

never are far away.

The long white road winds o’er the hill from

Fanad to Kilcar,

And winds apast Gweebara Bay where the

deep sea-waters are —

Where the long grey boats go out by night to

fish beyond the bar.

I’ll lie by the beach the livelong day, where the

foreshore dips to the sea —

When the sun is red on the golden gorse as once

it used to be;

And, O! but it’s many an olden thought will

come up in the heart of me.

For the friends of my youth shall gather

around, the friends that I knew of old,

The olden songs will be sung to me and the old,

old stories told

Beside the fire of my father’s house when the

nights are long and cold.

‘Tis there that I’ll pass my years away, back in

my native land;

In my father’s house by Rosses’ shore that lies

by Dooran strand,

Where the hills of ancient Donegal rise up on

either hand.

THE FARMER’S BOY

[Every May, a great number of Donegal youths, whose ages range from twelve to fifteen years, go to the hiring fair of Strabane in the Co. Tyrone, and there, in the market-place, they are sold like cattle to the highest bidder. Their wages range from 31 to 35 /s for six months, and they have to work about eighteen hours a day.]

WHEN I went o’er the mountains a farmer’s boy

to be,

My mother wept all morning when taking leave

of me;

My heart was heavy in me, but I thrept that I

was gay:

A man of twelve should never weep when going

far away.

In the country o’er the mountains the rough

roads straggle down,

There’s many a long and weary mile ‘twixt

there and Glenties town;

I went to be a farmer’s boy, to work the season

through,

From Whitsuntide to Hallowe’en, which time

the rent came due.

When virgin pure, the dawn’s white arm stole

o’er my mother’s door,

From Glenties town I took the road I never

trod before;

Come Lammas tide I would not see the trout

in Greenan’s Burn,

And Hallowe’en might come and go, but I

would not return.

My mother’s love for me is warm; her house

is cold and bare:

A man who wants to see the world has little

comfort there;

And there ‘tis hard to pay the rent, for all you

dig and delve,

But there’s hope beyond the mountains for a

little man of twelve.

When I went o’er the mountains I worked for

days on end,

Without a saul to cheer me through or one to

call me friend;

With older mates I toiled and toiled, in rain

and heat and wind,

And kept my place. A Glenties man is never

left behind.

The farmer’s wench looked down on me, for she

was spruce and clean,

But men of twelve don’t care for girls like lads

of seventeen;

And sorrow take the farmer’s wench! her

pride could never hold

With mine when hoeing turnip fields with

fellows twice as old.

And so from May to Hallowe’en I wrought and

felt content,

And sent my wages through the post to pay my

mother’s rent;

For I kept up the Glenties name, and blest,

when all was done,

The pride that gave a man of twelve the

strength of twenty-one.

THE DUG-OUT

DEEPER than the daisies in the rubble and the

loam,

Wayward as a river the winding trenches

roam,

Past bowed, decrepit dug-outs leaning on their

props,

Beyond the shattered village -where the

lightest limber stops;

Through fields untilled and barren, and ripped

by shot and shell, —

The bloodstained braes of Souchez, the

meadows of Vermelles,

And poppies crown the parapet that rises from

the mud —

Where the soldiers’ homes — the dug-outs —

are built of clay and blood.

Our comrades on the level roofs, the dead men,

waste away

Upon the soldiers’ frontier homes, the

crannies in the clay;

For on the meadows of Vermelles, and all the

country round,

The stiff and still stare at the skies, the quick

are underground.

STRAF’ THAT FLY

(Bully-Grenay.)

THERE’S the butter, gad, and horse-fly,

The blow-fly and the blue,

The fine fly and the coarse fly,

But never flew a worse fly

Of all the flies that flew

Than the little sneaky black fly

That gobbles up our ham,

The beggar’s not a slack fly,

He really is a crack fly,

And wolfs the soldiers’ jam.

So straf’ that fly! our motto

Is “Straf’ him when you can.”

He’ll die because he ought to,

He’ll go because he’s got to,

So at him, every man!

THE STAR SHELL

( Loos )

A STAR-SHELL holds the sky beyond

Shell-shivered Loos, and drops

In million sparkles on a pond

That lies by Hulluch copse.

A moment’s brightness in the sky,

To vanish at a breath,

And die away, as soldiers die

Upon the wastes of death.

AFTER THE WAR

WHEN I come back to England,

And times of Peace come round,

I’ll surely have a shilling,

And maybe have a pound.

I’ll walk the whole town over,

And who shall say me nay,

For I’m a British soldier

With a British soldier’s pay.

I only joined for fun,

Never joined for profit —

The Army pay is good,

But, God! there’s little of it.

When I come back to England

I won’t be half a swell —

Ribbons for the scrapping

At Loos and New Chapelle.

I’ll search the whole town over

To find another trade,

And be a blooming boot-black

On Charing Cross parade.

I will not leave for fun —

The change will bring me profit.

The Army pay is good,

But, God! there’s little of it.

A SOLDIER’S PRAYER

GIVENCHY village lies a wreck, Givenchy

Church is bare,

No more the peasant maidens come to say

their vespers there.

The altar rails are wrenched apart, with rubble

littered o’er,

The sacred, broken sanctuary-lamp lies smashed

upon the floor;

And mute upon the crucifix He looks upon it

all —

The great white Christ, the shrapnel-scourged,

upon the eastern wall.

He sees the churchyard halved by shells, the

tombstones flung about,

And dead men’s skulls, and white, white bones

the shells have shovelled out;

The trenches running line by line through

meadow fields of green,

The bayonets on the parapets, the wasting

flesh between;

Around Givenchy’s ruined church the levels,

poppy-red,

Are set apart for silent hosts, the legions of

the dead.

And when at night on sentry-go, with danger

keeping tryst,

I see upon the crucifix the blood-stained form

of Christ

Defiled and maimed, the merciful on vigil all

the time,

Pitying his children’s wrath, their passion and

their crime.

Mute, mute He hangs upon His Cross, the

symbol of His pain,

And as men scourged Him long ago, they

scourge Him once again —

There in the lonely war-lit night to Christ the

Lord To call,

“Forgive the ones who work Thee harm. O

Lord, forgive us all.”

DUG-OUT PROVERBS

HERE are the Old Sweats sayings. He tells the

tale of his trade —

Gleanings from trench and dug-out, battle,

fatigue, parade.

‘Tis said the Boche has pluck enouh. Of this

I have no doubt,

But see him in the darkest light until you’ve

knocked him out.

Your dug-out took you hours to build. Got

broken in a minute!

A rotten shame! Be thankful, son, your carcass

isn’t in it.

And if one shelters you a night tend it roof and

rafter,

And make it better than it was — for those who

follow after.

“The trench is calm,”you say, my son. The

Boche is keeping quiet.

Then keep your rifle close at hand. We soon

shall have a riot.

A soldier’s life is risky; it may end damn quick.

Well, let it!

Since we get five francs every week we’ll burst

it when we get it.

You may cough and sneeze in your dug-out,

but you can’t go anywhere.

There’s little health around the house — the dead

are lying there.

You may dig as deep as a spade can dig, but

the Boche’s eye can tell

Where the khaki moles have plied their trade,

and the beggars burrow well.

Pray to God when the dirt* flies over and

the

country flops about,

But stick to your dug-out all the same until

you’re ordered out.

When guns are going large a bit and sending

gifts from Krupp,

You’ve got to keep your napper low, but keep

your spirits up.

These are the dug-out maxims which the “Old

Sweats”fling about,

For the better education of the “rooky “newly

out

- Trench term for shells.

MATEY

(Cambrin, May, 1915.)

NOT comin’ back to-night, matey,

And reliefs are comin’ through,

We’re all goin’ out all right, matey,

Only we’re leavin’ you.

Gawd! it’s a loody sin, matey,

Now that we’ve finished the fight,

We go when reliefs come in, matey,

But you’re stayin’ ‘ere to-night.

Over the top is cold, matey —

You lie on the field alone,

Didn’t I love you of old, matey,

Dearer than the blood of my own

You were my dearest chum, matey —

(Gawd! but your face is white)

But now, though reliefs ‘ave come, matey,

I’m goin’ alone to-night.

I’d sooner the bullet was mine, matey —

Goin’ out on my own,

Leavin’ you ‘ere in the line, matey,

All by yourself, alone.

Chum o’ mine and you’re dead, matey,

And this is the way we part,

The bullet went through your head, matey,

But Gawd! it went through my ‘eart.

Music has always been an expression not only of emotion, but of popular culture, and the outbreak of WWI was no small inspiration for the many songwriters, lyricists and musicians, as well as the soldiers themselves. Though patriotism and morale remained a key topic for songs throughout the war and beyond, they also revealed the particular mood of the time from which they derive. From the patriotic “Keep the Home Fires Burning” to the enthusiastic strains of “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary” to the satirical “Oh, What a Lovely War!”, soldiers in the trenches and the people waiting for them back home used music to shape and mold the reactions to the brutality and tragedy–and inspiration–of war.

In tonight’s episode of Downton Abbey, Mary, accompanied at the piano by her sister Edith, uses the sentimental song, “If You Were the Only Girl (In the World)” to subtle express her sorrow and longing for Matthew. Written in 1916 by Nat D. Ayer with lyrics by Clifford Grey, the song evidently became a very popular wartime tune, as it is referenced in quite a few books written during WWI:

Ninety-Six Hours’ Leave by Stephen McKenna

THE Semiramis orchestra was beginning to play a second encore, when the girl in the white dress appeared at the top of the steps. “If you were the only girl in the world and I were the only boy,” she hummed to herself, as she came down into the lounge. The orchestra was unaffectedly bored with the song; it had been played once at luncheon, twice at tea, and now this was the fourth time since seven o’clock. Prince Christoforo, however, did not share their boredom; it was at his request that they were giving the encore.

Suddenly the Prince left his seat and approached the girl in white.

“If you’re looking for a chair,” he said, “there are four unoccupied ones over there.”

The girl turned at sound of his voice, still gravely nodding time to the music.

“‘ If I were the only girl in the world . . .’”

“And I were the only boy,” he answered, with a smile.

“I should like to dance, only I suppose people would stare.”

The Queen of Psalissa by George A. Birmingham

The king’s faith was very touching; but Gorman still maintains that he was not far wrong about Mme. Ypsilante’s feelings. She might not actually have preferred Konrad Karl’s death; but it is certain that she did not want to see him married to Miss Donovan.

The king drew a last mouthful of smoke from his cigar and then flung the end of it into the sea.

“Gorman, what is it that one of your great English poets has so beautifully said? ‘If you were the only girl in the world, and I were the only boy!’—that is Corinne and me. ‘A garden of Eden just made for two ‘—that is Paris. I have always admired the English poets. It is so true, what they say!”

Way of Revelation:a Novel of Five Years by Wilfrid Ewart

Rosemary Meynell went across to the bureau, unlocked the small drawer as before, and took from it the Louis Quatorze snuff-box. This she handed to Upton.

“Thank you,” he said with a disagreeable smile; “but these little things aren’t given up quite so easily as all that, you know. However, if you want any more . . . pleased to oblige at any time!”

Silence followed, during which the girl gazed steadily in front of her with an expression of fine contempt. The meanness of the man’s soul had never revealed itself as now!

Upton began to hum the words of a popular revue air, tapping in time to it with his foot.

“If you were the only girl in the world

And I …”“Well, the rest doesn’t matter,” he broke off. “You’re not, you see,”

The Things We Are by John Middleton Murry

He fed in a first floor tea-room full of Sunday couples who had reached the stage of sentimental silence. It was strange, he thought, how their attitudes ran to type. The man leaned back on the red plush seat that ran round the wall; the woman leaned her head on his shoulder. She was always on his right, and her right hand was always fingering his sleeve, his watch-chain or his coat lapel. Even the fair-haired man in pince-nez who was solemnly vamping out “If you were the only girl in the world” on the reluctant piano submitted to the ritual. A girl in pink, with a wad of black hair low down on her pasty neck, had flung her arm round his shoulder and was perched insecurely on all that remained of the stool.

There was even a gory adaptation of the song entitled “If you were the only Boche in the Trench”

Tune: “If you were the only Girl in the World.”

If you were the only Boche in the trench,

And I had the only bomb,

Nothing else would matter in the world that day,

I would blow you up into eternity.

Chamber of Horrors, just made for two,

With nothing to spoil our fun;

There would be such a heap of things to do,

I should get your rifle and bayonet too,

If you were the only Boche in the trench

And I had the only gun.

Piero Jahier and the Italian Soldier Songs

|

| Piero Jahier |