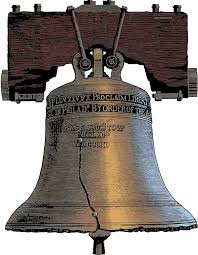

la campana venne fusa in una fonderia di Whitechapel, quartiere popolare di Londra. Era stata realizzata nel 1751 per celebrare il cinquantenario della Carta dei Privilegi redatta da William Penn, cui si deve l’estrema tolleranza dello stato della Pennsylvania. Sulla calotta, le parole del capitolo XXV, verso X, del Levitico: “E proclamerete la libertà in tutte le terre e a tutti gli abitanti”. La frase risuona profetica.

Una volta giunta dall’altra parte dell’oceano, però, si scoprì sulla campana una crepa tale da dover procedere ad una seconda colata. Furono i fabbri Pass e Stow a proseguire con l’operazione, aggiungendo i loro nomi a mo’ di firma sotto l’iscrizione primitiva. Nonostante la nuova fusione il solco è rimasto e attraversa tutt’oggi la Liberty Bell: una ferita, simile a quelle sparse sul corpo di tanti combattenti americani, tramutatasi in simbolo universale di indipendenza e democrazia.

I rintocchi della Liberty Bell hanno accompagnato i momenti principali della Storia degli Stati Uniti. Nel 1774 avevano aperto il Primo Congresso Continentale, con le 13 colonie riunite per contrastare le restrizioni commerciali imposte dal governo inglese (gli Intolerable Acts). Un anno dopo avevano annunciato la conclusione della vittoriosa battaglia dei patrioti a Lexington e Concord. Nel 1837 la campana era infine diventata simbolo del movimento abolizionista contro la schiavitù.

L’ultimo scampanellio della Liberty Bell ha augurato Happy Birthday al presidente George Washington nel 1846. La profonda crepa, allargatasi nel corso degli anni, ha però compromesso le capacità della campana, che da allora non è più stata impiegata, nel timore che si rompesse.

Tradition tells of a chime that changed the world on July 8, 1776, with the Liberty Bell ringing out from the tower of Independence Hall summoning the citizens of Philadelphia to hear the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence by Colonel John Nixon.

The Pennsylvania Assembly ordered the Bell in 1751 to commemorate the 50-year anniversary of William Penn’s 1701 Charter of Privileges, Pennsylvania’s original Constitution. It speaks of the rights and freedoms valued by people the world over. Particularly forward thinking were Penn’s ideas on religious freedom, his liberal stance on Native American rights, and his inclusion of citizens in enacting laws.

The Liberty Bell gained iconic importance when abolitionists in their efforts to put an end to slavery throughout America adopted it as a symbol.

As the Bell was created to commemorate the golden anniversary of Penn’s Charter, the quotation “Proclaim Liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof,” from Leviticus 25:10, was particularly apt. For the line in the Bible immediately preceding “proclaim liberty” is, “And ye shall hallow the fiftieth year.” What better way to pay homage to Penn and hallow the 50th year than with a bell proclaiming liberty?

Also inscribed on the Bell is the quotation, “By Order of the Assembly of the Province of Pensylvania for the State House in Philada.” Note that the spelling of “Pennsylvania” was not at that time universally adopted. In fact, in the original Constitution, the name of the state is also spelled “Pensylvania.” If you get a chance to visit the second floor of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, take a moment to look at the original maps on the wall. They, too, have the state name spelled “Pensylvania” (and the Atlantic Ocean called by the name of that day, “The Western Ocean”). The choice of the quotation was made by Quaker Isaac Norris, speaker of the Assembly.

Centered on the front of the Bell are the words, “Pass and Stow / Philada / MDCCLIII.” We’ll get to Pass and Stow in a bit.

The Crack

There is widespread disagreement about when the first crack appeared on the Bell. Hair-line cracks on bells were bored out to prevent expansion. However, it is agreed that the final expansion of the crack which rendered the Bell unringable was on Washington’s Birthday in 1846.

The Philadelphia Public Ledger takes up the story in its February 26, 1846 publication:

“The old Independence Bell rang its last clear note on Monday last in honor of the birthday of Washington and now hangs in the great city steeple irreparably cracked and dumb. It had been cracked before but was set in order of that day by having the edges of the fracture filed so as not to vibrate against each other … It gave out clear notes and loud, and appeared to be in excellent condition until noon, when it received a sort of compound fracture in a zig-zag direction through one of its sides which put it completely out of tune and left it a mere wreck of what it was.”

The Bell as Icon

The Bell achieved its iconic status when abolitionists adopted the Bell as a symbol for the movement. It was first used in this association as a frontispiece to an 1837 edition of Liberty, published by the New York Anti-Slavery Society.

It was, in fact, the abolitionists who gave it the name “Liberty Bell,” in reference to its inscription. It was previously called simply the “State House bell.”

In retrospect, it is a remarkably apt metaphor for a country literally cracked and freedom fissured for its black inhabitants. The line following “proclaim liberty” is, “It shall be a jubilee unto you; and ye shall return every man unto his possession, and ye shall return every man unto his family.” The Abolitionists understood this passage to mean that the Bible demanded all slaves and prisoners be freed every 50 years.

William Lloyd Garrison’s anti-slavery publication The Liberator reprinted a Boston abolitionist pamphlet containing a poem about the Bell, entitled, The Liberty Bell, which represents the first documented use of the name, “Liberty Bell.”

The Bell and the Declaration of Independence

In 1847, George Lippard wrote a fictional story for The Saturday Currier which told of an elderly bellman waiting in the State House steeple for the word that Congress had declared Independence. The story continues that privately he began to doubt Congress’s resolve. Suddenly the bellman’s grandson, who was eavesdropping on the doors of Congress, yelled to him, “Ring, Grandfather! Ring!”

This story so captured the imagination of people throughout the land that the Liberty Bell was forever associated with the Declaration of Independence.

The truth is that the steeple was in bad condition and historians today highly doubt that the Bell actually rang in 1776. However, its association with the Declaration of Independence was fixed in the collective mythology.

Bell as Symbol

After the divisive Civil War, Americans sought a symbol of unity. The flag became one such symbol, and the Liberty Bell another. To help heal the wounds of the war, the Liberty Bell would travel across the country.

Starting in the 1880s, the Bell traveled to cities throughout the land “proclaiming liberty” and inspiring the cause of freedom. We have prepared a photo essay of its 1915 journey to the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco.

A replica of the Liberty Bell, forged in 1915, was used to promote women’s suffrage. It traveled the country with its clapper chained to its side, silent until women won the right to vote. On September 25, 1920, it was brought to Independence Hall and rung in ceremonies celebrating the ratification of the 19th amendment.

To this day, oppressed groups come to Philadelphia to give voice to their plight, at the Liberty Bell, proclaiming their call for liberty.

History of the Bell

On November 1, 1751, a letter was sent to Robert Charles, the Colonial Agent of the Province of Pennsylvania who was working in London. Signed by Isaac Norris, Thomas Leech, and Edward Warner, it represented the desires of the Assembly to purchase a bell for the State House (now Independence Hall) steeple. The bell was ordered from Whitechapel Foundry, with instructions to inscribe on it the passage from Leviticus.

The bell arrived in Philadelphia on September 1, 1752, but was not hung until March 10, 1753, on which day Isaac Norris wrote, “I had the mortification to hear that it was cracked by a stroke of the clapper without any other viollence [sic] as it was hung up to try the sound.”

The cause of the break is thought to have been attributable either to flaws in its casting or, as they thought at the time, to its being too brittle.

Two Philadelphia foundry workers named John Pass and John Stow were given the cracked bell to be melted down and recast. They added an ounce and a half of copper to a pound of the old bell in an attempt to make the new bell less brittle. For their labors they charged slightly over 36 Pounds.

The new bell was raised in the belfry on March 29, 1753. “Upon trial, it seems that they have added too much copper. They were so teased with the witticisms of the town that they will very soon make a second essay,” wrote Isaac Norris to London agent Robert Charles. Apparently nobody was now pleased with the tone of the bell.

Pass and Stow indeed tried again. They broke up the bell and recast it. On June 11, 1753, the New York Mercury reported, “Last Week was raised and fix’d in the Statehouse Steeple, the new great Bell, cast here by Pass and Stow, weighing 2080 lbs.”

In November, Norris wrote to Robert Charles that he was still displeased with the bell and requested that Whitechapel cast a new one.

Upon the arrival of the new bell from England, it was agreed that it sounded no better than the Pass and Stow bell. So the “Liberty Bell” remained where it was in the steeple, and the new Whitechapel bell was placed in the cupola on the State House roof and attached to the clock to sound the hours.

The Liberty Bell was rung to call the Assembly together and to summon people together for special announcements and events. The Liberty Bell tolled frequently. Among the more historically important occasions, it tolled when Benjamin Franklin was sent to England to address Colonial grievances, it tolled when King George III ascended to the throne in 1761, and it tolled to call together the people of Philadelphia to discuss the Sugar Act in 1764 and the Stamp Act in 1765.

In 1772 a petition was sent to the Assembly stating that the people in the vicinity of the State House were “incommoded and distressed” by the constant “ringing of the great Bell in the steeple.”

But, tradition holds, it continued tolling for the First Continental Congress in 1774, the Battle of Lexington and Concord in 1775 and its most resonant tolling was on July 8, 1776, when it summoned the citizenry for the reading of the Declaration of Independence produced by the Second Continental Congress. However, the steeple was in bad condition and historians today doubt the likelihood of the story.

In October 1777, the British occupied Philadelphia. Weeks earlier all bells, including the Liberty Bell, were removed from the city. It was well understood that, if left, they would likely be melted down and used for cannon. The Liberty Bell was removed from the city and hidden in the floorboards of the Zion Reformed Church in Allentown, Pennsylvania, which you can still visit today.

Throughout the period from 1790 to 1800, when Philadelphia was the nation’s capital, uses of the Bell included calling the state legislature into session, summoning voters to hand in their ballots at the State House window, and tolling to commemorate Washington’s birthday and celebrate the Fourth of July.

The Bell Today

The Liberty Bell Center was opened in October, 2003. From the southern end, the bell is visible from the street 24 hours a day.

On every Fourth of July, at 2pm Eastern time, children who are descendants of Declaration signers symbolically tap the Liberty Bell 13 times while bells across the nation also ring 13 times in honor of the patriots from the original 13 states.

Each year, the bell is gently tapped in honor of Martin Luther King Day. The ceremony began in 1986 at request of Dr. King’s widow, Coretta Scott King.

Commenti recenti